Do Professional Managers Understand Buybacks?

A Financial Times article highlights concerns about buybacks — and raises questions about professional managers

⚡ Highlights:

The perception of stock buybacks continues to be plagued by misunderstandings and outright errors.

After a discussion last week, we add more thoughts about the nature of professional investors, and note a key advantage of individual investors.

A Financial Times article from last week adds more color to both discussions.

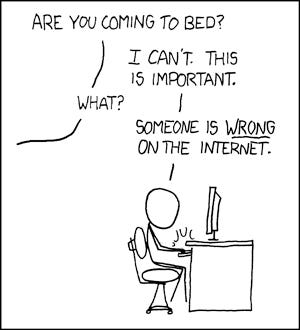

I try not to be “Internet outrage guy”. But there is one topic that gets me worked up more than any other: dividends and stock buybacks.

Admittedly, there are many more important topics that could be discussed on the Internet. But the discussion around stock buybacks — which now reaches into the political arena — contains so many errors that it becomes infuriating.

It’s worth covering those errors given how important capital returns are to the investing process. It’s also worth highlighting a recent article which shows how deep into the financial industry the misconceptions around buybacks reach — and what that might mean for the rest of us.

source: xkcd.com

Buybacks Bad, Dividends Good

There’s clearly a conception that dividends are good and buybacks are bad. Dividends provide income to investors; in some cases those investors are widows and orphans. But buybacks, as the left-leaning Americans for Financial Reform put it in 2021, “exacerbate the racial wealth gap, worsen economic inequality, and divert resources from the real economy which harms workers.”

That passage comes from a political organization, of course. But the conception exists in the investing world as well. The most successful author1 on a well known investing site focuses on stocks that offer high dividend yields. A subscription covering high buyback yields would not do nearly as well. Indeed, the very concept of a “buyback yield” feels a bit fuzzy, while dividend yields sit on the quote page of every stock on most major websites.

But of course, the discussions around buybacks and stock dividends generally miss the core point: they’re essentially the same thing. A stock buyback is simply a dividend with reinvestment set as the default, instead of as an option.

We’ll put the math in a footnote2, but the intuitive argument alone can work. In each case, the company is returning capital to shareholders.

To be sure, there are important differences. Buybacks are seen as more tax-efficient, because dividends are taxed at the time of return, while taxes on the ownership increase created by a buyback can be deferred. Particularly in the U.S., dividends are issued quarterly, and a cut is seen as a highly negative event; buybacks can be and are much more irregular.

But, again, these are simply two forms of capital return, which for each individual shareholder actually are interchangeable (you can turn a dividend into a buyback, or vice versa). And these forms of capital return aren’t even that material. A 5% return of capital — via either method — simply means that control over cash equaling 5% of your investment transferred from the company to you. That’s it.

About the only way that change in control can be that valuable is if the management team running the company is so untrustworthy as to make investors demand their cash back. At that point, you might as well take all of it back, and sell your position.

Yet there are investors who will only buy stocks that pay a dividend. Some see dividend stocks as safer or simply better investments. It can be an expensive mistake to make. Over the past ten years, the Vanguard Dividend Appreciation ETF VIG 0.00%↑, now the largest dividend-focused ETF, has returned 177% including dividends. The S&P 500 Total Return index is up 202%; the NASDAQ 100 Total Return index more than 400%.

Can Individual Investors Win?

We talked just last week, about the potential data advantage afforded institutional investors in the modern environment. When MediaAlpha MAX 0.00%↑ plunged on a seemingly minor catalyst (weak earnings from key customer Progressive $PGR), I noted the ‘old’ way of seeing that plunge might have been to see an opportunity, to assume that a shareholder was liquidating and thus pressuring a relatively thinly-traded stock.

Nowadays, however, the more logical explanation is to assume that someone somewhere knows something. There’s so much data out there, and so much access to it, that simply waiting for the 10-Q isn’t necessarily a viable strategy. It’s stale data, like trying to live-bet an NBA game while watching on a ten-minute delay.

That in turn raises a question which actually became relatively prevalent toward the latter half of the 2010s: can individual investors truly beat the market? There’s a famous quote from Warren Buffett that suggests that smaller investors indeed have an edge — but only in smaller stocks [emphasis ours]:

If I had $10,000 to invest, I would focus on smaller companies because there would be a greater chance that something was overlooked in that arena. The highest rates of return I’ve ever achieved were in the 1950s. I killed the Dow. You ought to see the numbers.

But I was investing peanuts then. It’s a huge structural advantage not to have a lot of money. I think I could make you 50% a year on $1 million. No, I know I could. I guarantee that. But you can’t compound $100 million or $1 billion at anything remotely like that rate.

It’s always weird to contradict Buffett, but while I agree about the advantage of a smaller portfolio, I’ve never believed that ~50% annualized returns were remotely achievable over any significant period of time. Even by the time Buffett said this, in 19993, he no doubt had been out of the micro- and small-cap world for quite a while.

And that world changed substantially in the interim. Buffett’s argument that “I killed the Dow” in the 1950s seems more due to the fact that active investors of all stripes weren’t nearly as good. There wasn’t the same amount of data, there wasn’t anything like the current access to that data, there wasn’t the same amount of effort, and there were essentially no hedge funds fishing in the same proverbial waters.

In the 60-plus years since, there’s been an ongoing arms race, led by institutional investors, to amass more data, create better models, and to make better decisions. The shift to passive investing — which accelerated in the 2010s — and, as importantly, the shift to the recommendation of passive investing to individuals, seemed a response to this arms race, an admission that individual investors were at best unlikely to keep pace.

Amateurs Versus Pros

But there’s an interesting flipside to the data argument: the people argument. Many individual investors who truly enjoy the market, who find 10-K filings fascinating, who enjoy the challenge of stock-picking and who dream of a May weekend in Omaha, would likely be stunned to find that many professional investors do not at all share their passion.

And so when studies show how rare it is for funds to beat the market (this Twitter thread has a solid compilation of those studies), one intriguing question is whether the issue is the incentives of those funds, rather than the impossibility of outsmarting the market. Those incentives often lead managers to simply track the index as closely as possible, and to take consensus bets.

“Nobody ever got fired for buying IBM IBM 0.00%↑” is a popular saying (though presumably less popular these days). But a version certainly is applicable to the financial world as well. I remember meeting with a well-compensated manager in 2016 and discussing the U.S. presidential election. At the time, it was widely assumed that a Trump victory would be a negative for the U.S. stock market4. The manager largely dismissed the possibility of such an upset — but shrugged and said that, were it to happen, "we’ll just get defensive.” In other words, basically tracking the index was good enough (and, as it turned out, getting defensive in November 2016 was a terrible strategy).

To be sure, many professional investors do the work and have the data. But even for those investors, incentives are generally skewed toward being in the market. Many of them knew, for instance, that the late 2020/early 2021 rally was reaching the point of insanity. There hadn’t been as many attractive short opportunities in two decades.

Yet hedge funds have now underperformed in both up markets and down markets. Fees obviously are a key part of the underperformance, but in my experience, many of those funds — data advantage or not — aren’t doing the work the right way.

Would You Invest With These Guys?

Last week, the Financial Times published an article entitled “Record buyback spree attracts shareholder complaints.” It’s an impressive piece in that it marshals so many of the erroneous arguments against buybacks in one place — and sources those arguments from fund managers around the world. The article notes that, in 2022, the world’s 1,200 biggest public companies repurchased $1.3 trillion in stock — “almost as much as they paid out in dividends.”

The idea that those share repurchases could attract complaints from shareholders is beyond bizarre. But the arguments detailed to the FT highlight a rather stunning misunderstanding of a key investing concept by managers who absolutely should know better.

There’s the executive compensation concern, from Euan Munro, chief executive of Newton Investment Management, a subsidiary of BNY Mellon BK 0.00%↑ with $100 billion in assets under management5:

We would prefer buybacks to be less prevalent…Used badly, [buybacks] can be used to manipulate [earnings per share] numbers upwards to meet medium-term management incentive targets at the expense of investments that might be important to a company’s long- term health.

This is a common argument: buybacks increase both the stock price and earnings per share in a way that dividends don’t, and so they’re simply a way to pay off corporate managers who are incentivized to increase either the share price and/or EPS.

Of course, that argument assumes that a) the board of directors is using those metrics for incentive compensation and b) ignoring the impact of repurchases on the stock price and EPS and/or c) foregoing needed investments anyway. In other words, the argument assumes that the board and management of the company are not aligned with shareholders. That’s the core problem, not the buybacks. Put another way, buybacks don’t unjustly enrich executives; boards do.

A fund manager at Federated Hermes has literally zero understanding of the basic point we made above:

The dividend is just the dividend: grandma benefits, the long-term holder [benefits]. Buybacks benefit traders, hedge funds, senior executives [and] near-term share prices.

But this one, from a UK-based manager at Fidelity, is even worse [emphasis ours]:

“As a shareholder you feel like you never actually get the reward” with buybacks. “If the market is nonplussed by it then, as a shareholder, you are worse than square one, as the company has typically used up their cash.”

The buyback is the reward, of course.

Another manager makes the common argument that buybacks “destroy value” because they are made at poor prices:

Buybacks only create value for remaining shareholders and strong relative performance when shares are cheap and there are no better uses of that cash which would generate higher returns. Most buybacks help optical [earnings per share] growth but destroy value.

As the article notes, companies with big buybacks have underperformed recently. But it’s important to remember two key points.

The first is that, by definition, no share buyback can ever be executed at a price disagreeable to an active shareholder. That shareholder chose to own the stock6 at the same price at which the company bought back shares. If, in retrospect, the buyback was poor, the shareholder made the far bigger mistake.

That aside, an investor can — as our math in footnote number 2 shows — sidestep the impact of any repurchase by simply selling her portion of the repurchased shares. Yes, there’s a lag between the disclosure of buybacks, and on occasion companies buy back stock even ahead of an ugly quarter; the method isn’t foolproof. But, here, too, the bigger problem is that the stock the investor owned tanked.

Taking Responsibility

There does seem to be a common thread in these arguments: they suggest that buybacks are far more material than they actually are, and in some cases far more material than the original investment decision itself. And so perhaps it’s not terribly surprising that professionals see an opportunity to create a bogeyman beyond their control, one more reason why middling performance is someone else’s fault.

To be fair, not all professionals see it that way. The FT article quoted Jim Tierney of AllianceBernstein AB 0.00%↑:

I don’t know how we’ve gotten to this point politically, but the idea that buybacks are a bad thing, or simply a way to manipulate your stock, I don’t think could be further from the truth.

We couldn’t agree more. In fact, we wish more professional investors felt this way. Then again, perhaps the rest of us have a better chance to make money if they don’t.

As of this writing, Vince Martin has no positions in any securities mentioned.

Disclaimer: The information in this newsletter is not and should not be construed as investment advice. Overlooked Alpha is for information, entertainment purposes only. Contributors are not registered financial advisors and do not purport to tell or recommend which securities customers should buy or sell for themselves. We strive to provide accurate analysis but mistakes and errors do occur. No warranty is made to the accuracy, completeness or correctness of the information provided. The information in the publication may become outdated and there is no obligation to update any such information. Past performance is not a guide to future performance, future returns are not guaranteed, and a loss of original capital may occur. Contributors may hold or acquire securities covered in this publication, and may purchase or sell such securities at any time, including security positions that are inconsistent or contrary to positions mentioned in this publication, all without prior notice to any of the subscribers to this publication. Investors should make their own decisions regarding the prospects of any company discussed herein based on such investors’ own review of publicly available information and should not rely on the information contained herein.

ie, an author who offers a subscription service through the platform, which not all authors on SA do.

You own 1% of a $1 billion company, a $10 million position. The company pays a 5% dividend, a total distribution of $50 million. The stock falls 5% to account for the lower cash payout. You now own 1% of a $950 million company, a position worth $9.5 million, plus you received a $500,000 dividend, so you’re back at $10 million in total value.

Suppose, instead, the company executes a 5% buyback. Your position is still worth $10 million, as you own 1.053% of a company worth $950 million. You can sell a 0.053% stake, get $500K in cash, and — as in our dividend example — own a 1% stake worth $9.5 million and have $500K in cash.

I haven’t been able to find a direct source for the quote; some attribute it to a Berkshire shareholder letter, but that appears to be incorrect.

Indeed, overnight S&P 500 futures were down as much as 5% on Election Night; the index finished the following day up more than 1% and kept rallying.

The AUM figure is from Wikipedia, admittedly but appears directionally correct.

Obviously, the shareholder didn’t necessarily buy the stock the same day, but in a liquid market not selling the stock is essentially the same decision.

I agree that buybacks are more tax-efficient, given how we tax dividends today.

I still don't like them, because buybacks assume that management and boards are good judges of when shares are undervalued. That's not really their job, nor are they expected to be good at it. The Board's job is strategy, capital allocation and oversight (among other things), management's job is execution. We've also seen, in recent years, plenty of examples of when they've exercised staggeringly poor judgment on the question of when shares are over-/under-valued (e.g., BBBY). I don't blame them for it, since I don't expect them (or anyone else, for that matter) to be experts on the subject.

If (and this is a big if) Congress can legislate to exempt DRIPPed dividends from taxation, then all returns of capital to shareholders can be done as dividends; and the decision of whether to be taxed now (pocket the dividend) or taxed later (DRIPping the dividend now and sell the shares at some future date), is left in the hands of the owners of the capital, not in the Board's hands and (often) imperfect judgment.

FWIW, I agree that proposals like taxing buybacks and its idiot cousin, taxing unrealized capital gains, are stupid beyond belief.

In a certain way this article should not exist because reasonable people should already know and understand those things.

It will always be a mistery to me why buybacks and dividends create such a big and never-ending debate.