Fundamentals: Cash Flow Versus Earnings

The two metrics seem similar — but can be very different

In theory, the value of an investment is equal to the sum of all future cash flows, discounted back to present value. In other words, a business should be worth the total of the cash flow it will generate in the future, with the important caveat that dollars generated in the future are much less valuable than those generated today.

Even for those who subscribe to this theory, there are some obvious issues. It makes sense to discount future cash flows, certainly: in all but the most unusual environments, a dollar in 2034 is worth much less than a dollar in 2024. But by how much should we discount those future cash flows — and why? Expectations around inflation and interest rates are of course factors. If an investor can get 5% interest from the U.S. government for one year, almost by definition a dollar 12 months from now has to be worth less than 95 cents today.

But this same theory argues that investors also need to account for risk: a higher-risk investment should have a higher discount rate. Of course, that simply gets us back to the starting point: how high a discount rate? And why?

Is Tesla a risky investment? Bears would argue that of course it is: any auto manufacturer is risky. Bulls would retort that of course it isn’t: it’s a diversified business with multiple high-margin revenue streams led by a charismatic, historically successful CEO.

Of course, all this ignores the much bigger problem. How, exactly, is an investor supposed to know what future cash flows look like? Indeed, the biggest critique of discounted cash flow models (often referred to as ‘DCFs’) is that they are subject to the “garbage in, garbage out” problem.

Garbage In, Garbage Out

A DCF is useless if the inputs to the model — the projected future cash flows — are wrong. In fact, it can be worse than useless. By creating a present value for the business (which in turn is used to value the stock), the model creates a false sense of accuracy. And it doesn’t take much for inputs to create vastly different outcomes.

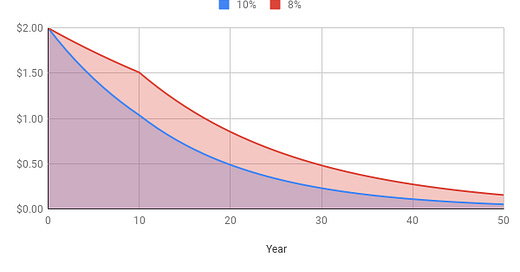

Imagine a business with free cash flow per share of $2.00, which is projected to grow 5% annually, where the discount rate is 8%. A rough DCF model (which assumes 2% growth in perpetuity after 10 years) values each share at $42.84.

Lower near-term growth to 3%, however, and raise the discount rate to 10%, and valuation drops all the way to $27.39, even keeping the same long-term growth rate of 2%.

In the chart below, the colored area represents the actual free cash flow per share being generated over time, discounted back at the respective discount rates. As we can see, being wrong up front means an investor is still wrong decades later, even on a present value basis:

source: author

Still, the theory behind discounted cash flow provides a useful framework for understanding what active equity investing is actually supposed to be: finding businesses that are going to generate more cash flow than the market currently projects. Those projections are built into the stock price (though, as seen multiple times over the past four years, the connection between future cash flows and the actual stock price in the market can become strained). The fun and difficulty in stock-picking is trying to assess where the market is (hopefully) wrong.

There’s one more interesting question to consider however: why, exactly, are we discussing cash flow and not earnings?

Why Cash Flow Is ‘Better’ Than Earnings

After all, it’s earnings that get the focus from investors and, notably, the financial media. The period that begins a few weeks after the end of each calendar quarter is called “earnings season”, not “cash flow season”. In theory (at least this theory), cash flows drive stock valuations. In practice, it’s earnings that seem to drive stock prices.

The semi-accurate answer to the question is that cash flow is real, and earnings are not. A dollar in cash can be reinvested in the business or distributed to shareholders via share buybacks and/or dividend payments.

In contrast, earnings are essentially an accounting fiction. $100 million in cash flow is $100 million going into the corporate bank account. $100 million in earnings is a number on a ledger.

One way to understand this is to work down the P&L from EBITDA, (earnings before interest, taxes, depreciation, and amortization). Above the EBITDA line, there are differences between earnings and free cash flow: stock-based compensation, for instance, is deducted from GAAP earnings (though SBC is excluded from adjusted figures reported by most companies these days). But, roughly speaking, EBITDA is a good starting point for both earnings and free cash flow.

After that, however, the metrics notably diverge. To get to free cash flow from EBITDA, the business deducts:

cash interest payments;

cash paid for taxes; and

capital expenditures, or actual cash paid for physical assets

These are all obviously real, concrete expenses. In contrast, to get to earnings from EBITDA, the business deducts:

interest expense under accounting rules, which may include non-cash expenses like the amortization of debt issuance costs;

the book tax rate, which may differ notably from the actual cash paid (for instance, if the company runs a loss that creates a deferred tax asset);

depreciation, another non-cash expense which accounts for the reduction in value of existing physical assets;

and amortization of previous spending, most notably of intangible assets acquired in an acquisition.

And in those deductions, businesses have a perhaps surprising amount of flexibility. For instance, major tech companies last year chose to extend the useful life of previously purchased servers. This had the effect of lowering annual depreciation expense, since the same initial cost was spread over more years. By one estimate, the shift added some $10 billion to their total reported earnings.

Indeed, bearish takes and even outright short sales can be based on a consistent gap between earnings and free cash flow. That gap suggests that the company is using accounting techniques to make earnings look better, because there are no such techniques for improving free cash flow (other than outright fabrication of the statement itself). Companies like IBM and General Electric have been targeted for aggressive accounting, particularly around adjusted numbers. And the ability for companies to manipulate earnings has led to scandals in the past, with the early 2000s trio of Enron, Tyco, and Worldcom the most prominent.

Those scandals have been minimized substantially by the Sarbanes-Oxley Act of 2002, which assigned personal responsibility for accurate accounting to top corporate officers. Still, there are legal ways in which companies can make not just adjusted earnings, but GAAP (Generally Accepted Accounting Principles) earnings, more favorable. That aside, many aspects of earnings are based on actual judgments by corporate officers, whose biases are clear.

There is no bias in the cash flow statement. Again, it represents the dollars going into (or out of) the corporate accounts. In that context, it would seem like cash flow is the far more important metric.

Why Earnings Exist

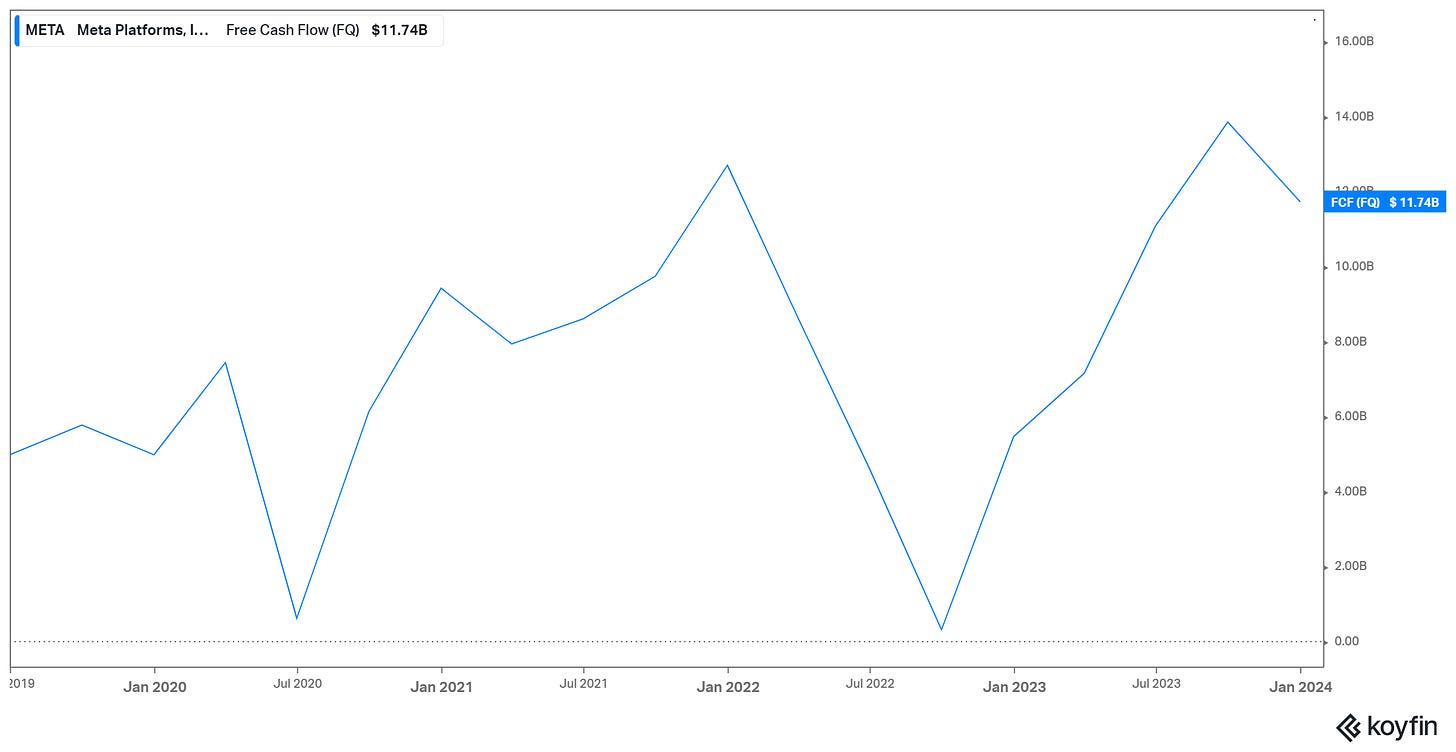

But cash flow has a big problem. It’s lumpy:

source: Koyfin

Above is a five-year chart of quarterly free cash flow from Facebook owner Meta Platforms $META. The chart is hardly unusual.

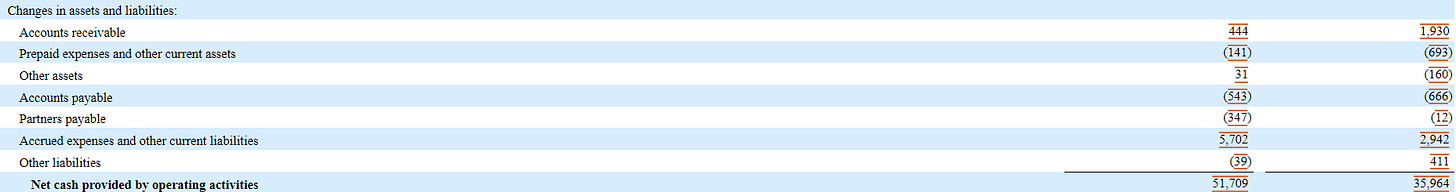

Free cash flow can swing wildly for many reasons. Changes in working capital ( current assets and liabilities like inventory, accounts payable and receivable, and accrued expenses) are a key part of free cash flow:

source: Meta 10-Q, Q3 2023

And those aspects of working capital move for reasons that have little to do with the underlying performance of the business. A significant payment might come in on October 1 instead of September 30, which boosts fourth quarter cash flow at the expense of the previous period. Inventories for retailers can fluctuate dramatically over the course of the year, building in the third quarter and then bottom in the first quarter, after the busy holiday period. For some businesses, the timing of bonus payments to employees is significant, and certainly enough to make free cash flow in that quarter much weaker.

Even taking the longer view, variability between years can be significant. Sotera Health $SHC is an interesting example. The parent of sterilization provider Sterigenics settled a huge lawsuit in 2022, which hit earnings but the payment wasn’t made until 2023. And below the operating cash flow line, capital expenditures have doubled, due to expansions at existing facilities and the construction of new ones.

source: Sterigenics 10-K

So Sotera’s free cash flow has plunged into the red, to a burn of $362 million in 2023 against an inflow of $179 million two years earlier. But that decline doesn’t necessarily reflect a similar change in the actual operations of the business.

The point of earnings is to construct a scenario in which immaterial working capital effects basically don’t matter, while the impact of larger corporate decisions (like capex or acquisitions) are spread out over a longer period. Indeed, this is exactly how depreciation works: the elevated capital expenditures in 2023 (which Sotera expects will continue this year before a drop-off in 2025) don’t lead to a sharp drop in reported earnings. Instead, depreciation rises over time, with the ‘hit’, as it were, from the capital expenditures extending across the useful life of these new facilities.

Why We Focus On Earnings

The broader point is that earnings may be ‘fake’ relative to cash flow, but in some sense they are actually more ‘true’. The accounting regime around earnings creates a construct in which the ongoing, consistent operations of the business are actually measured.

Certainly, earnings are not perfect. There are judgments and errors (it’s possible, for instance, that servers won’t last as long as tech companies now believe, which will require accelerated depreciation in future years if the value of those servers is written off to zero). There is outright manipulation, even of the petty kind: a 2018 study found significant evidence that quarterly earnings per share numbers are rounded up to the nearest penny rather than down.

But it’s useful to imagine a world where free cash flow was the headline metric, instead of earnings. It would be bedlam. Businesses would make huge efforts and incur high expense to pull in cash just before the end of the quarter or year end. Analyst estimates would often be off by hundreds of millions of dollars, solely because of the timing of a capital project or the receipt of a sizeable check.

In contrast, earnings provide a smoother picture, one that generally speaking is (roughly) accurate based on the efforts of everyone involved. And the point of that smoother picture is not just to tell investors what has happened, but what will happen. It provides the ability to see trends, to understand changes in the business, and to better forecast the future. It is, after all, the future that matters for investors.

As of this writing, Vince Martin has no positions in any securities mentioned.

Disclaimer: The information in this newsletter is not and should not be construed as investment advice. Overlooked Alpha is for information, entertainment purposes only. Contributors are not registered financial advisors and do not purport to tell or recommend which securities customers should buy or sell for themselves. We strive to provide accurate analysis but mistakes and errors do occur. No warranty is made to the accuracy, completeness or correctness of the information provided. The information in the publication may become outdated and there is no obligation to update any such information. Past performance is not a guide to future performance, future returns are not guaranteed, and a loss of original capital may occur. Contributors may hold or acquire securities covered in this publication, and may purchase or sell such securities at any time, including security positions that are inconsistent or contrary to positions mentioned in this publication, all without prior notice to any of the subscribers to this publication. Investors should make their own decisions regarding the prospects of any company discussed herein based on such investors’ own review of publicly available information and should not rely on the information contained herein.

Great article and breakdown--thanks!

Thanks for another brilliant article!