Fundamentals: GameStop Versus Archegos

There are similarities between Roaring Kitty and Bill Hwang

Last week, we floated the question of whether Keith Gill, a.k.a ‘Roaring Kitty’ committed insider trading. The answer seems to be no, for the simple reason that Gill is not an insider.

There is a more interesting question, however: is Gill committing market manipulation?

(Disclaimer: The author has no legal training and nothing in this post should be relied on as legal advice.)

What Is Market Manipulation?

U.S. Supreme Court justice Potter Stewart famously said of pornography that “I know it when I see it.” There’s a similar sense with market manipulation, a crime whose definition remains somewhat uncertain, despite a 1950 law specifically prohibiting the manipulation of security prices.

The SEC, on its investor protection website, provides a colloquial definition:

Market manipulation is when someone artificially affects the supply or demand for a security (for example, causing stock prices to rise or to fall dramatically)

The key word there is “artificially”. The Commodity and Futures Trading Commission, which, as its name suggests, regulates commodities and futures, offers a four-part test for market manipulation. The last two parts are “that artificial prices existed” and “that the accused caused the artificial prices”.

Already, the crime of market manipulation seems a bit fuzzy. The SEC and CFTC don’t necessarily agree on the exact definition, and even the CFTC’s test came from case law, rather than direct guidance from Congress. But the sense from both regulators is that market manipulation comes when traders try to influence the price rather than the value of the instrument.

This is why an activist short report from Hindenburg Research is not market manipulation (despite many protestations to the contrary). When Hindenburg took aim at Icahn Enterprises last May, its detailed report was an attempt to influence the value of IEP stock. The firm made a detailed argument that the stock was overvalued; its goal was to make other investors agree, which in turn would lower the price of IEP, providing a profit on the trade.

The purpose was not to simply shock the market and make investors dump stock as quickly as possible. That likely would be considered illegal: case law to this point suggests that while short selling is completely above board, it becomes manipulative when “combined with some sort of misinformation transmitted to the market.”

Notably, at least per the CFTC test, that “misinformation” has to be purposeful. If Hindenburg had, for instance, badly miscalculated Icahn Enterprises’ net asset value, that likely would not be considered market manipulation. If the firm had, however, forged documents claiming that IEP didn’t actually own the businesses it claimed to, that almost certainly would be judged manipulation (and fraud as well).

The “artificial price” definition does provide a broad sense of what regulators do see as illegal. Standard “pump and dumps” certainly qualify. In those activities, traders often disseminate false information with the aim to drive the stock up before (the ‘pump’) and then sell as close to the top as possible (the ‘dump’)1.

Here, it’s quite obvious that the traders are trying to manipulate the price, not the value. In contrast, a coordinated, factual, effort to highlight the value in a stock — say, through a company’s investor relations program, or an activist campaign — isn’t manipulative. The goal of those investors (as with Hindenburg) is to make the price of the stock reflect their perceived value, not to make the price go up through false information.

Fake takeover offers occur from time to time2: those are classic, obvious market manipulation. So are fake news articles reporting a takeover bid, like the one that briefly spiked Twitter stock in 2015. “Spoofing”, in which traders enter bids they have no intention of exercising in order to influence prices, was specifically banned in the Dodd-Frank Act of 2010 (enacted in response to the financial crisis).

These market manipulation violations all make sense: they are, as Justice Stewart might have put it, quite easy to see.

But the line between what is and what isn’t manipulation does get fuzzy, as two recent examples show. One is GameStop. The other is a trial underway as we speak.

Archegos: $200 Million To $36 Billion To Zero

In 2013, Bill Hwang established Archegos Capital, a family office designed to manage the wealth he’d created during a past career as a hedge fund manager. As Bloomberg detailed in 2021, Hwang was incredibly successful. In 2016, according to a source, a single trade on Netflix made a profit of nearly $1 billion. By the next year, another source estimates Hwang’s portfolio had risen ~20x, to about $4 billion.

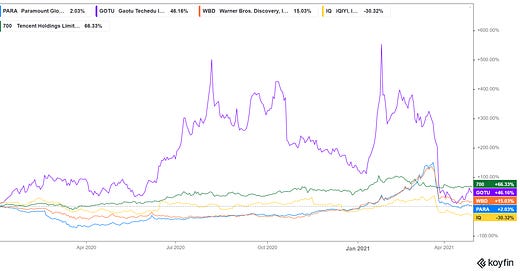

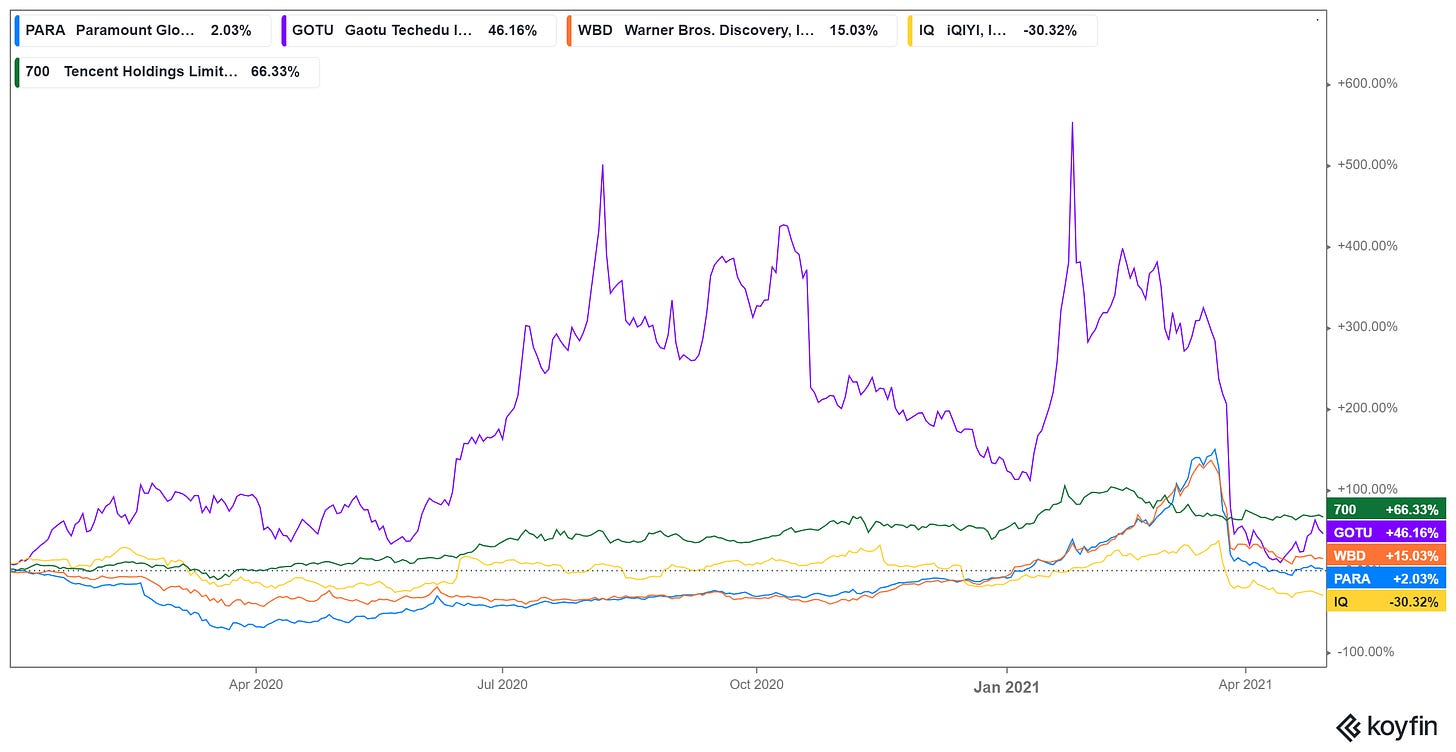

But at some point in 2020, Hwang began to press his bets. He ran his portfolio reportedly at about 5x leverage, and began to concentrate in a few stocks. According to a 2022 indictment, Archegos owned:

over 70% of outstanding shares in GSX Techedu (now known as Gaotu Techedu GOTU 0.00%↑);

over 60% of Discovery Communications Class A and over 30% of Class C (that company is now Warner Bros. Discovery WBD 0.00%↑);

over 50% of iQiyi IQ 0.00%↑ and ViacomCBS (renamed Paramount Global PARA 0.00%↑);

over 45% of Tencent $TCEHY.

No one knew Archegos owned these kinds of stakes. Hwang used swaps with nearly every major investment bank to essentially hide his economic ownership3. The multiple agreements also meant that each bank didn’t know how leveraged the fund was. In fact, Archegos had $163.5 billion in gross market exposure, on the back of just $36 billion in assets. That’s leverage of more than 4 to 1.

On its own, that kind of leverage isn’t unusual for family offices and hedge funds. But banks usually are only willing to lend at that kind of leverage for funds running a hedged long/short strategy. Archegos, instead, was plowing ever-greater capital into a small number of stocks. Its buying alone was driving those stocks higher:

source: Koyfin

In March of 2021, ViacomCBS announced a convertible debt offering, clearly designed to take advantage of the soaring stock price created by Archegos’ steady buying. The offering tanked the stock, and that started a domino effect that wiped out the fund within days. All told, investment banks lost about $10 billion in the collapse, with about $5.5 billion coming from Credit Suisse. CS would eventually be acquired by UBS with the Archegos losses a contributing factor. Hwang was indicted in 2022, and charged with running a “massive market manipulation scheme”.

Did Bill Hwang Manipulate The Market?

Where market manipulation gets a bit fuzzy is in the fact that almost every investing strategy (to some extent) moves the market. Hwang’s concentrated, leveraged portfolio in early 2021 is an extreme example of a simple fact: buying (or selling) a security moves the price of that security. Even a single retail investor, buying a relatively small position, can make a stock price change.

There are cases where intent isn’t quite clear. In 2018, the CFTC lost a market manipulation case surrounding interest rate swaps; the defendant successfully argued that his firm, DRW, was trying to take advantage of a mispricing. The judge agreed that, even when DRW was submitting over 2,500 bids in an effort to move the price of its swaps higher, the resulting price was not artificial. DRW thought it had an edge, and kept trying to communicate that information to the market.

In the case of Archegos, there’s a clear question that Bloomberg columnist Matt Levine asked in 2022:

Bill Hwang is not some dope; he is a long-time hedge fund manager with a Tiger Management pedigree… Bill Hwang presumably did not want to lose all his money. What was his exit plan? How did he think the story would end?

Even the judge in the case has wondered:

“What did he want? What did he want to achieve? Being a big shot, I suppose that’s possible, but it doesn’t seem to me that was his aim,” the judge, Alvin Hellerstein, said at a hearing [in 2023]. “I can’t figure out his aim.”

Indeed, this is part of the defense strategy in the trial, with Hwang’s lawyers calling the case the “most aggressive open market manipulation case” ever. Reuters noted the prosecution’s “unusual manipulation theory”, and quoted an attorney who noted “the defense will argue those buys were bona fide”. Inded, they did: the opening statement said that Hwang had “the courage of his convictions”, and believed deeply in the companies in which he invested.

Even with multiple Archegos executives testifying against Hwang — and one openly admitting to market manipulation in court — it’s hard not to have some sympathy for that argument. Higher stock prices didn’t lead to higher fees; Hwang was investing his own cash4. The stocks may have been ‘pumped’ by his buying, but it wasn’t as if Archegos was disseminating false information or even any information. Many major players on Wall Street had never heard of Archegos until it collapsed5.

The prosecution’s argument is that Hwang wanted to be a “legend on Wall Street”, which itself highlights the point that there isn’t a clear financial aspect to the alleged crime. There was no simple way for Hwang to cash out without destroying his portfolio. Indeed, it took a single convertible offering for the entire house of cards to collapse. It seems like at least part of Hwang’s motivation was true belief. As a well-known investor in a retail chain might have put it, he liked the stocks.

Market Manipulation In GameStop

In 2021, as GameStop was peaking, Levine noted noted that an illegal pump and dump in theory could be executed by a small group without lying, perhaps through an “expensive newsletter”, and still be considered market manipulation. And so the obvious question is whether a large group of traders, operating through a subreddit, could be guilty of the same.

Levine didn’t really the answer the question (and given the tenor at the time, we can’t blame him). We’d guess that if you asked a junior SEC lawyer to build a case for market manipulation against, say, the most popular and strident Reddit posters, she could probably do it quite easily. We’d also guess that if you asked a senior SEC lawyer to actually prosecute that case, she would decline, likely with an expletive or two.

But there is a logical argument that GME bulls are committing market manipulation. The first two parts of the CFTC’s four part test (which wouldn’t necessarily apply, but as far as we can tell provides the broader framework established in case law even in SEC cases) are perhaps more interesting:

that the accused had the ability to influence market prices;

that [the accused] specifically intended to do so.

Really, the question is about the first part: do Redditors have the ability to influence market prices? Clearly, they intend to do so. And we’d argue, even after yet another stock offering from GameStop today, that the GME stock price is artificial. The fourth part — “that the accused caused the artificial prices” too seems to hold, if you believe the first part is satisfied.

To be sure, this is mostly a fun, theoretical example. The idea that GMEBull237 on Reddit would be dragged into court for market manipulation remains far-fetched. But there is an irony pointed out by multiple observers: it seems pretty clear that the GameStop bulls screaming the loudest about market manipulation (by short sellers) are the ones who are coming the closest to actually manipulating the market.

Is Keith Gill In The Clear?

One month ago, Keith Gill, posted a picture on X of a man leaning forward in a chair to play a video game. In two trading days, GME nearly tripled. Three weeks later, he posted a screenshot of his position in the stock, a portfolio then valued at roughly $180 million. A livestream followed, during which GME tanked 40% as Gill apparently didn’t give his fans quite what they were hoping for. Along the way, Gill has posted an endless series of memes on Twitter, each with tens of thousands of likes and many thousands more in views.

It is truly incredible that any of this matters, that memes from a former middle manager at an insurance company in Massachusetts has led to a month with average daily volume just over 100 million shares (in the range of $2.5 billion per day) and allowed GameStop to now raise over $3 billion in cash.

But is it illegal? It’s close enough that Morgan Stanley unit E*Trade reportedly considered kicking Gill off its platform. Yet, as the Wall Street Journal noted last week, it’s difficult to see Gill’s conduct crossing the line:

Gill’s recent actions don’t fall into that framework. None of his posts have been explicit endorsements of investing in GameStop or claims about the company’s financial prospects. It is unclear whether Gill has sold his shares, or whether he is still amassing a giant GameStop stake.

That was written before the livestream. In it, Gill was quite obviously being careful. He completely legally talked his book, discussing his optimism toward the company’s turnaround. And it’s hard to believe Gill amassed a position worth $180 million without getting some excellent legal advice6.

At the same time, this isn’t really good. It’s not what a market regulator wants to happen. It’s not really what market participants want to happen. Investors and companies generally want to create sustainable long-term value, not ephemeral short-term peaks.

Frenzied trading, and raising cash directly from retail investors at likely inflated prices, is not the sign of a healthy market. Levine famously wrote on February 1, 2021 that “if we are still here in a month I will absolutely freak out [emphasis in original].” He’s poked fun at his own quote multiple times since, but we indeed “are still here” more than three years later.

And to some degree, we are still “here” because of Gill. He had the ability to create a higher price in GME, and did so. The key distinction is whether this higher price is an artificial price. Gill would argue (and in his livestream did argue) otherwise. But of course he pretty much has to say that in public. An admission that the price is artificial might well be considered an admission of guilt.

But what’s fascinating about the confluence of Gill’s return and Hwang’s trial is that the two investors have so much in common. One might well ask of Gill the same question that judges and writers have asked of Hwang: what’s the endgame? For Gill, is the prestige of being the ultimate Redditor/ meme investor the true goal? He easily could have walked away — quietly — with a nine-figure fortune. He instead has opened himself to exposure, and made a huge bet (with short-term call options on a highly volatile stock) that does have some risk of collapsing. It’s still a long way to June 21, when Gill’s options expire.

Is the aim for Gill — like prosecutors argue of Hwang — more power and prestige?

source: X.com/RoaringKitty

It’s a truly stunning symmetry. We have two men, Hwang and Gill, who have clearly manipulated the market — if not in the legal sense, then clearly in the practical sense. And yet, for both, we still don’t know if what they did was legal, or how their stories will end.

As of this writing, Vince Martin has no positions in any securities mentioned.

Disclaimer: The information in this newsletter is not and should not be construed as investment advice. Overlooked Alpha is for information, entertainment purposes only. Contributors are not registered financial advisors and do not purport to tell or recommend which securities customers should buy or sell for themselves. We strive to provide accurate analysis but mistakes and errors do occur. No warranty is made to the accuracy, completeness or correctness of the information provided. The information in the publication may become outdated and there is no obligation to update any such information. Past performance is not a guide to future performance, future returns are not guaranteed, and a loss of original capital may occur. Contributors may hold or acquire securities covered in this publication, and may purchase or sell such securities at any time, including security positions that are inconsistent or contrary to positions mentioned in this publication, all without prior notice to any of the subscribers to this publication. Investors should make their own decisions regarding the prospects of any company discussed herein based on such investors’ own review of publicly available information and should not rely on the information contained herein.

The best-known recent executor of the “pump and dump” is probably Jordan Belfort, made famous in the movie The Wolf of Wall Street.

In 2015, a single trader reportedly issued fake buyouts for three different companies. A supposed offer for Textron TXT 0.00%↑ in 2020 led to criminal charges against another trader.

A swap is basically a contract with a bank in which the bank technically owns the stock (and thus is reported as the beneficial owner in SEC filings) but the counterparty is responsible for covering losses and benefiting from gains.

Hwang allegedly pushed his employees to invest alongside him, but their contribution was minimal; again, at the peak, Archegos’ portfolio value was $168 billion.

Incredibly, given that the firm lost over $5 billion, the first time Credit Suisse’s head of investment banking and its chief risk officer had ever known of Archegos was after CS issued a $2.7 billion margin call that, obviously, was never met. (That information comes from Credit Suisse’s own report on its losses in Archegos.)

As the Journal pointed out, Gill himself has experience: long before GME, he was chief compliance officer for an investment advisory firm.

My unpolished view is that this isn't manipulation and that it is entirely victimless. It is so bad (substantively) that it is good (legally). Or, rather, no one could mistake it for sober analysis. It is literally for entertainment purposes only and followers get what they came for. My $0.02 here https://chrisdemuthjr.medium.com/nihilism-sputters-f77bef32c2e2

In trying to answer what was Hwang’s ultimate motive, the answer might lie in the name he chose to give to his family office. “Archegos” means “leader” or “boss” in Greek.