Investing Lessons From The Walgreens Stock Collapse

Walgreens provides a fascinating case study for investors wishing to avoid value traps

In response to the madness of the last few years we’ve decided to start a new series called Fundamentals. In this series we will be looking at business case studies and investing topics from an educational perspective. If you enjoy this type of write-up, let us know. We’d love to hear what you think!

In July 2015, shares of Walgreens Boots Alliance WBA 0.00%↑ neared $100. At that price, WBA stock was expensive, but not ridiculously so. A few months later, the company delivered fiscal 2016 guidance of $4.25 to $4.55 earnings per share. That outlook implied a forward price-to-earnings multiple of about 22x. Price to free cash flow multiples were roughly the same.

WBA received a premium to the market because it seemed like a business worth paying up for. It was a so-called Dividend Aristocrat, a title bestowed on companies that have increased their dividends for at least 25 consecutive years. At the time, Walgreens’ streak was 40 years long. Those dividends were only a small part of the benefits of owning the stock. Since the mid-1970s, WBA had provided total returns of over 86,000%. In roughly 40 years, $1,000 would have turned into $860,000.

Meanwhile, the company’s healthcare focus made it a defensive business, one less exposed to fluctuations in the economy. The merger of Walgreens and Alliance Boots, a European pharmacy chain, closed in 20141, promising cost savings for years to come. In the context of Walgreens’ history and future, it was not unreasonable, in July 2015 to see WBA as one of the better stocks in the market.

Walgreens Stock Collapses

But WBA stock was not one of the best in the market. In fact, among large-cap names2, it would prove to be one of the worst.

In early August 2015, the stock set an all-time high just below $97. Since that point, WBA dropped 77%. Its market capitalization fell from over $100 billion to under $20 billion today. The stock is still part of the Dow Jones Industrial Average but it will likely be pulled at some point in the near future. Walgreens’ market cap of $18.4 billion is now less than half that of the next smallest DJIA constituent, Travelers Companies TRV 0.00%↑, and roughly 1/150th of the index’s largest stock, Apple AAPL 0.00%↑.

It’s worth repeating. This would have been a scenario that few, if any, investors would have contemplated in August 2015. Indeed, in early August, short interest in WBA stock was about $1 billion. The 12 million shares sold short were a little over 1% of total shares outstanding (per data from Koyfin). That isn’t nothing by large cap standards but it’s not huge either.

What’s more incredible about the plunge in WBA is how relentless it’s been. Over the eight years, there have been only two significant rallies in Walgreens stock — and they reversed quickly:

source: Koyfin with author highlighting of 2018 and 2020-2021 rallies

It’s been eight years of continuous selling. 10-year total returns, assuming dividends were reinvested, are negative 46%. Had an investor taken the dividends simply in cash, she’d still be down about 30%. Over the same period, the S&P 500, including dividends, has more than tripled.

Lessons From Walgreens

The story of the collapse in Walgreens stock is not a simple one. Walgreens’s numbers weren’t faked. Its industry has faced pressures, certainly, but it’s not as if regulators shut down pharmacies or a significant competitor entered the market. As noted, valuation at that peak was not unreasonable. WBA was never a bubble stock, or anywhere close. Rather, WBA’s stunning decline came from a confluence of factors.

Above all, the eight-year performance of Walgreens stock is a reminder that stock-picking is complicated and difficult. Individual investors can find an edge against professional investors. But, for the most part, those professional investors are doing the work; individual investors must do the same. WBA shows the danger in failing to do that work.

Understanding The Business

One of the simplest lessons from the collapse in Walgreens stock is that an investor absolutely must understand, completely, the business she is buying. Walgreens has proven to be a business that, on the surface, looks ‘safe’, while hiding dangerous risks.

In Walgreens’ case, the bull case for the business seemed simple. Consumers always need pharmaceuticals. Given aging populations in the U.S. and the United Kingdom (where Boots was headquartered), they would likely need more prescriptions.

In the mid-2010s, in particular, there was a lot of noise about Amazon AMZN 0.00%↑ potentially entering the market. In 2018, the e-commerce giant acquired PillPack for $750 million, a move that seemed to suggest aggressive competition against Walgreens, CVS CVS 0.00%↑, and Rite Aid. After that deal, several Wall Street analysts slashed their price targets on Walgreens stock.

But Amazon’s presence in the market, five years after the PillPack purchase, remains relatively small (though its January launch of RxPass, a membership benefit for generic prescription drugs, does represent a threat). The problem for Walgreens has not been its share of the market, but the market itself.

What has happened on the pharmacy side is relatively simple. Over time, insurance companies continue to reduce reimbursement rates for prescription drugs. The U.S. federal government has done much the same: in Medicare and Medicaid, for instance, the average net price for drugs (after rebates and discounts) fell relatively sharply between 2009 and 2018.

When WBA stock peaked in 2015, this risk was already well-known. But what happened is that Walgreens couldn’t cut costs fast enough to match lower prices, whether in terms of labor expense or in switching customers to lower-cost generics. That issue in fact continues: on the company’s second quarter earnings call in March, chief financial officer James Kehoe said that reimbursement rates had dropped 15% year-over-year (and in an inflationary environment at that).

Meanwhile, Amazon did prove to be disruptive: but to the retail side of Walgreens’ business. Next-day and, then, same-day delivery options created significant competition for products like over-the-counter medications (on which Walgreens historically had been able to place a high markup). Same-store retail sales for Walgreens in the U.S. turned negative in fiscal 2016, and didn’t return to growth until fiscal 2020. Performance overseas — in both pharmacy and retail — was even worse than it was at home.

Looking Very Closely

These risks weren’t obvious just by looking at the performance of the underlying business. In the US pharmacy segment, Walgreens’ operating income increased through fiscal 2018, more than three years after the stock peaked. Operating margins did weaken that year, and fiscal 2019 was ugly, but the havoc of the pandemic made interpreting subsequent results problematic.

Source: Koyfin

Meanwhile, taking the long view, it doesn’t look like this business is that challenged. Margin pressure has been a problem, but fiscal 2018 adjusted operating income in the U.S. retail pharmacy business was $5.0 billion, against a peak of $5.9 billion four years earlier. Operating margins went from a high of 6.54% in fiscal 2017 to 4.61% in fiscal 2022 — a decline of less than two percentage points.

To be sure, performance overseas has been much more disappointing, and essentially an amplified reflection of the challenges in the U.S. But even there, revenue declines have been in the single-digits, and total operating profit erosion between FY17 and FY22 was about 20%, not that much worse than what was seen in the U.S.

Earnings per share have declined, but not plunged. Fiscal 2016 adjusted EPS came in at $4.59; the figure this year should be right about $4.

The Earnings Multiple

In other words, Walgreens earnings per share fell about 13%. The value of Walgreens stock plunged 77%. Put another way, Walgreens stock collapsed even though the Walgreens business did not.

There are two explanations for this seeming contradiction. Neither perfectly tells the story, but both provide important context for this (and other) situations.

The first explanation is that the multiple assigned to Walgreens’ earnings compressed dramatically. Again, back in 2015, WBA stock traded for roughly 22x the following year’s earnings. Right now, based on consensus estimates for fiscal 2024, WBA trades at just six times net earnings.

Roughly speaking, a 22x multiple is one that implies consistent, if not necessarily spectacular, growth. Here are some of the well-known stocks trading in the range at the moment:

Nike NKE 0.00%↑

Starbucks SBUX 0.00%↑

Pinterest PINS 0.00%↑

Walmart WMT 0.00%↑

A 6x multiple, however, is very different. In the S&P 500 right now, there are only seven stocks with lower forward multiples than Walgreens. Five are highly cyclical businesses. Investors fear profits will turn south when broader macroeconomic weakness arrives. Those aside, WBA is lumped in with the likes of AT&T T 0.00%↑ and Verizon Communications VZ 0.00%↑, both long-time value traps with a still-high concentration of profits in their declining wireline businesses.

Basically, investors went from believing that Walgreens was one of the better businesses in the market to believing it was one of the worst. That in turn dramatically affected (and still affects) the price they are willing to pay for that business. In 2015, even investors who didn’t own WBA (again, the stock was not heavily-shorted relative to its size) believed its profits would grow over time. In 2023, the majority of investors believe those profits will shrink. Roughly speaking, given current current interest rates a business with no growth should trade in the range of 9x-10x earnings3.

WBA On The Way Down

Of course, that change in investor sentiment didn’t occur overnight. As a result, there are lessons to be learned from how investors treated WBA not just in 2015 and 2023, but in the interim as well.

No doubt many Walgreens shareholders kept holding their shares in the hope they would bounce back to a level where they could simply break even. This is a common investing mistake — but as the long-term chart shows, a highly dangerous one.

As the old saying goes, “the market doesn’t care what your cost basis is.” In other words, from a fundamental perspective, the price paid for a stock should be essentially irrelevant4. There was time for investors who owned WBA in 2015 to get out in the ensuing years before the worst of the collapse happened. The international business started flailing almost as soon as the merger with Boots closed. Same-store sales in retail (which exclude the benefit from new stores and the lost sales from closed locations) turned negative in fiscal 2016. Hindsight is 20/20, of course, but even at the time there were warning signs that many existing shareholders unfortunately failed to heed.

Many new shareholders joined along the way, of course. More than a few bought Walgreens stock because it had fallen and thus was “too cheap”. This is known as “anchoring bias”: buying a stock because an investor’s perception of value is ‘anchored’ to a past price. (It can of course cut both ways: avoiding a stock because it’s already gained 80% can be its own type of error.) The steadily lower WBA stock price was not a buying opportunity simply because it was 20%, then 40%, then 60% below past highs. Those lower lows occurred as the market updated the WBA stock price to account for new information — such as pressures on profit margins and weakness overseas.

Some investors likely bought WBA because of the dividend. They may still be doing so: Walgreens’ dividend yields 8.5% at the moment, the second-highest in the S&P 500 behind Altria MO 0.00%↑. But investors must remember that dividends aren’t incremental to stock returns; they come out of the stock price5. The day a cash dividend is paid, that cash leaves the business; as a result, the business almost by definition is worth exactly that amount less.

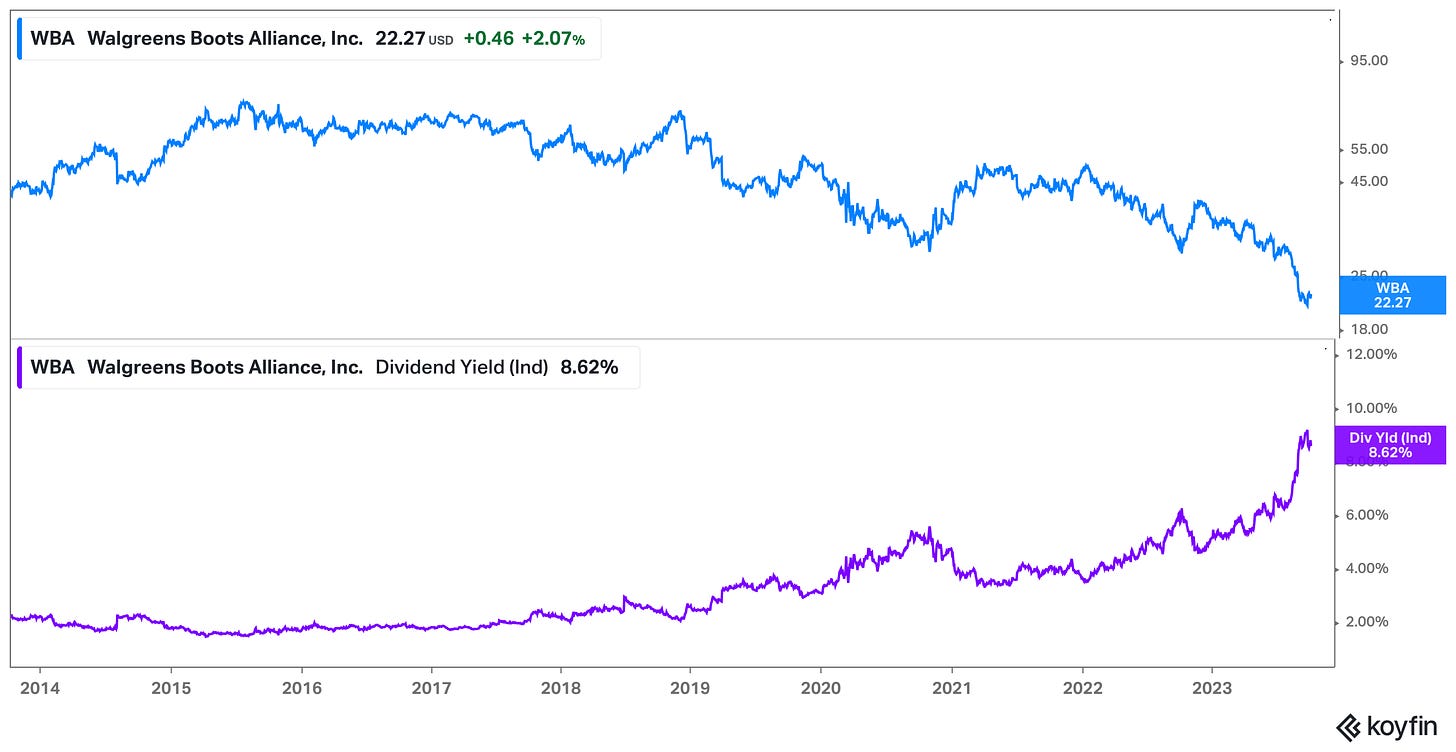

Indeed, WBA has proven to be a classic “yield trap”, in which investors chase a high dividend yield and suffer significant price depreciation in the process. That trend has only gotten worse:

source: Koyfin

Again, it was impossible to see this level of collapse coming from the 2015 peak. But there were warning signs in the business that could, and maybe should, have steered investors away. In many cases, common errors led those investors to ignore the warning signs and wind up in even deeper trouble.

A Complicated Story

There are other aspects of the Walgreens story that provide important lessons. The company is a cautionary tale when it comes to acquisitions, for instance. Walgreens spent over $20 billion for Boots. It tried to sell the business for less than $7 billion last year, only to find no takers. The company tried to buy all of Rite Aid, got out of that deal owing to regulatory issues, then spent $5.2 billion for about half of that chain’s stores. That deal, too, was a failure. The other half of Rite Aid (based on current bond prices as the company prepares for Chapter 11) is worth less than $1 billion.

But even the value destroyed by acquisitions (maybe something like $10 billion, when accounting for profits made from Boots and Rite Aid stores) is only a small part of the nearly $90 billion in equity value that’s been erased.

Slowing revenue growth is a factor; weaker profit margins are a factor. Debt on the balance sheet was a cause. So was reduced investor confidence. Pressure on the retail business mattered. Lower generic drug prices mattered.

Walgreens stock is such a fascinating cautionary tale because it’s such a complicated cautionary tale. Again, there was no single cause here. Several relatively small factors — modest margin compression, poor acquisitions, changing market dynamics, even debt on the balance sheet — combined to cause a plunge that very few investors saw coming.

Of course, there is a flip side to this story, which leads to a quite positive interpretation of what’s happened to WBA stock. Just as it doesn’t take that much for a stock to collapse, it doesn’t take that much for a stock to outperform.

After doing the work an investor could have seen the pressures on the Walgreens business in 2015 onward and realized that the businesses leading the industry were the insurance companies pressuring Walgreens’ margins. And she could have in turn bought UnitedHealth UNH 0.00%↑ (total returns of nearly 400% since the beginning of 2016), or Aetna (bought out at a premium by CVS), or Elevance Health ELV 0.00%↑ (formerly Anthem) which would have more than tripled her money.

The story of Walgreens is a cautionary tale, yes, but it’s also why stock-picking remains so fascinating and, in our opinion, so worthwhile. We still believe that individual investors have a good chance to beat the market if they do the work. In its own way, WBA shows how and why that is possible.

This article is not investment advice and is for information and entertainment purposes only. This article was written by Vince Martin, edited by Joe Marwood.

Walgreen acquired 45% of Boots in 2012, and the remaining 55% two years later.

‘Large-cap’ typically refers to market capitalizations of $10 billion or higher, though definitions may vary.

At 10x earnings, a zero-growth business in perpetuity would provide annual returns of 10% (since its profits are 1/10th of its market cap each year), so in the current interest rate environment, 10x seems like a reasonable estimate (again, roughly speaking).

Others might see it differently: for instance, famed value investor Ben Graham posited an 8.5x multiple for a no-growth business. Whatever the number a specific investor would choose, 6x clearly represents expectations for a decline.

To be fair, there are considerations, most notably around taxes, in which the cost basis matters. But in terms of appraising the fair value of a holding right now, whether the stock was bought at $10 or $100 should have basically no bearing.

There was a time when the stock actually stepped down by the amount of the dividend on its ex-dividend date, but that process has been somewhat smoothed out.

outstanding analysis....