Editor’s Note: This is another installment of our Fundamentals series, which aims to explain investing concepts. If you enjoy this series, let us know in the comments.

In 2019, Uber UBER 0.00%↑ went public. The company’s initial public offering was priced at $45 per share, which valued the company at $82 billion. Even that figure was a disappointment; the $45 price was at the low end of the range, and the year before two investment banks had pitched the company on a valuation of $120 billion.

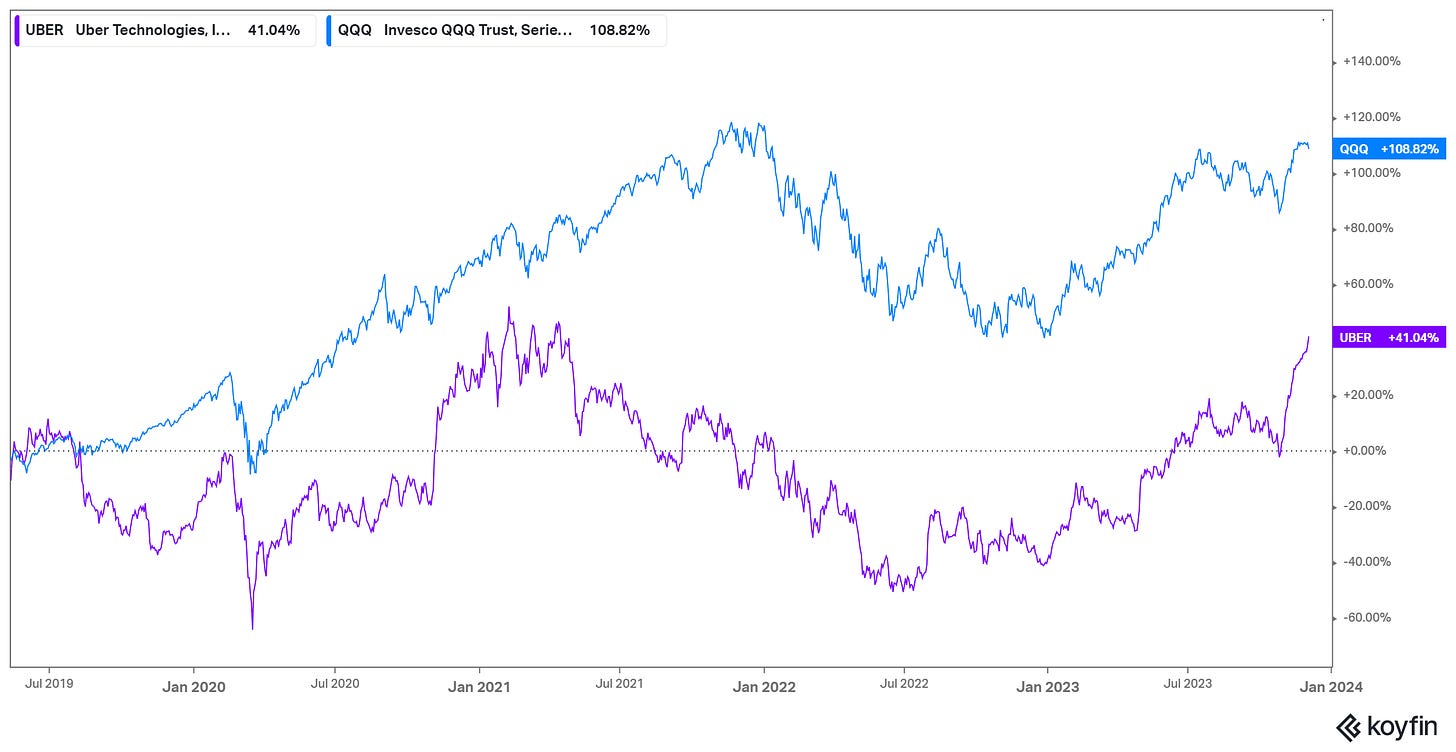

That valuation seemed insane. The $120 billion figure was higher than the market capitalization of established giants like 3M MMM 0.00%↑, 21st Century Fox (most of which would soon be acquired by Disney DIS 0.00%↑ for $71 billion), and Nvidia NVDA 0.00%↑. And indeed, Uber stock fell on its first day, and in four and a half years on the public market UBER has been a poor investment by the standards of large-cap tech peers:

source: Koyfin

But this performance is hardly what the stock’s most ardent skeptics would have predicted at the time of the IPO. To those skeptics, UBER was the sign of a tech market that had lost its mind, one in which valuation was meaningless. And a quick look at the company’s fundamentals seemed to confirm that argument.

In 2018, Uber did generate $11.27 billion in revenue. But it had $14.3 billion in expenses, not including $648 million in interest expense. Surely, a company posting a loss well past $3 billion wasn’t worth $8 billion, let alone $80 billion. Yet Uber has now reached that $120 billion valuation — and this week was selected to join the prestigious Standard & Poor’s 500 index.

Unprofitable Tech Stocks Keep Winning

UBER was far from the only high-growth, high-valuation name that aroused the ire of fundamentally-minded investors. Amazon.com AMZN 0.00%↑ faced questions about its valuation for most of the 2010s. SaaS (software-as-a-service) names like Salesforce.com CRM 0.00%↑, Adobe ADBE 0.00%↑, and Workday WDAY 0.00%↑ looked expensive and kept getting more expensive. Less mature software plays seemed even worse: many were valued not on profits, but on revenue, because they had no profits of which to speak.

And yet, overall, those stocks have sharply outperformed, even with investors last year showing more caution toward high valuations. The Invesco QQQ Trust Series 1 QQQ 0.00%↑, which tracks the tech-heavy, large-cap, NASDAQ 100 index, has been a far better investment than the S&P 500, which includes more old-line businesses, more dividend payers, and more value stocks:

source: Koyfin

Similarly, the Russell 1000 Growth Index has handily outperformed the Russell 1000 Value Index:

source: Koyfin

And, again, to many investors this simply did not make sense. The willingness of investors to pay 15x or 20x sales for high-growth businesses often was dismissed as a consequence of zero interest rates. With no ability to get returns from savings accounts or debt instruments, by this theory investors were forced to chase returns in the equity market at essentially any valuation.

This theory seemed validated last year when the Federal Reserve increased interest rates, and many high-flying growth stocks fell sharply. (UBER, for instance, plunged 41%.) But in 2023, growth is once again outperforming. That in turn suggests there’s another factor at play, and that investor willingness to pay up for growth has a logic to it beyond just low interest rates. And there is some logic: investors prize operating leverage.

What Is Operating Leverage?

Operating leverage is the rate at which increases in revenue turn into increases in profits. As with financial leverage, which we covered last week, operating leverage amplifies revenue growth. The higher a business’s operating leverage, the higher profits go as revenue rises.

There are businesses with low operating leverage. Relatively speaking, traditional retail businesses usually qualify. An accounting firm is another example: adding more business requires adding more accountants, and so profits generally increase at a rate similar to revenue.

Generally speaking, operating leverage is greatest with businesses with high fixed costs and low variable costs. A classic high operating leverage industry is airlines. To fly a 747 from New York to Los Angeles costs much the same whether the plane is empty or full; the only variable cost is fuel (which goes up owing to the extra weight of additional passengers). And so if a flight is breakeven at, say, 75 passengers, the airline loses substantial money if it sells 60 tickets — but at 90 tickets, the operating profit of the flight is not much lower than the revenue generated through the incremental 15 tickets.

As with financial leverage, operating leverage is mostly a good thing — but with a cost. The high operating leverage of an airline is why investors continue to buy shares of existing airlines and keep trying to start new ones: they can be absurdly profitable when well-run, and can grow earnings in an absolute hurry when times are good. Analysts expect United Airlines UAL 0.00%↑ to generate adjusted EPS of $9.76 this year, near quadruple the $2.52 print from the year before.

But the combination of operating leverage and macroeconomic risk is why airlines keep going bankrupt. Famously, Southwest Airlines LUV 0.00%↑ is the only major American carrier to have never declared bankruptcy. In the U.S., airlines only survived the coronavirus pandemic thanks to tens of billions of dollars in government aid. United’s adjusted EPS even in 2021 was a loss of nearly $14 per share, two years after it earned more than $12.

What Operating Leverage Means For Growth Stocks

Ideally, then, what investors would love to own is a business that has high operating leverage but lacks the downside risk of high fixed costs and/or cyclical exposure. And that is exactly what so many tech stocks of the last 20 years have offered.

Take Uber, for instance. One big reason for the company’s massive losses in 2018 was heavy promotional spending that was designed to capture customers for the long haul1. That spending had an inherent logic because a platform business like Uber has exceptionally high operating leverage: its profits soar as revenue grows.

The specific, numeric term for operating leverage is “incremental margins”: the percentage of an additional dollar in revenue that turns into operating income. For Uber, or other platform/marketplace businesses like Etsy ETSY 0.00%↑, incremental margins are exceptionally high. Just as it costs United very little to fly an extra passenger across the country, it costs Uber little to book an extra rideshare. Incremental margins are now 9% of bookings, meaning Uber gets an extra $9 in EBITDA for every $100 in customer spend — and that’s with driver and customer incentives and other factors.

But in terms of incremental leverage, even better than Uber is the SaaS business. Once a software platform has been developed, the cost of adding an extra user is minimal. It’s a bit of energy, a bit of storage spending, perhaps sales commissions and other factors. And because SaaS demand has grown and continues to grow, for the best SaaS companies the downside risk of high operating leverage — which only arrives when revenue declines — doesn’t really exist. No matter what interest rates are, it’s not hard to see why investors are willing to pay huge premiums to own that kind of business.

How Operating Leverage Makes The Fundamentals Work

The irony of the fundamental protestations against growth stock valuations is that it’s operating leverage that actually makes the fundamentals work. The same companies that looked foolishly overvalued just a few years ago now have grown into those past valuations.

Uber itself is an example. In 2018, the company posted an Adjusted EBITDA loss of $1.85 billion, more than 16% of revenue. This year, analysts expect positive Adjusted EBITDA of roughly $4 billion, nearly 11% of sales. That’s a 27 percentage point improvement in five years. And while that doesn’t mean Uber can expand margins by another 27 percentage points over the next five years, it’s clear that profits can continue to grow at a rate far higher than revenue.

The software sector has shown similar operating leverage, particularly with investors now demanding a focus on profitability over a focus on growing revenue. Salesforce is a perfect example: its operating margins expanded 850 basis points (8.5 percentage points) year-over-year in the third quarter. So impressive was the performance that the company’s own founder called it “pretty incredible” on the third quarter earnings call. Between fiscal 2021 (ending January) and fiscal 2024, Salesforce’s revenue should increase about 63%. Its operating income will jump roughly 180%, with margins soaring to 30% from 17%.

The ‘new’ Uber, perhaps is Snowflake SNOW 0.00%↑. The data software developer trades at nearly 24x trailing twelve-month revenue; on a GAAP (Generally Accepted Accounting Principles) basis, the company has lost nearly $900 million over the past four quarters. It has a valuation of $62 billion.

But there is a path for Snowflake to grow into that valuation, as operating leverage and high incremental margins drive quick profit growth. In 2021, Snowflake’s Adjusted EBITDA was modestly negative; by 2025, analysts expect margins above 15%. Adjusted net profit should more than triple this year, and with revenue still growing at more than 30% annually there’s plenty of room for that to continue. Even with a recent rally and such a nosebleed valuation, analysts still believe SNOW should gain more than 15% over the next twelve months.

Why Operating Leverage Makes Revenue Growth So Important

This is not to say that UBER, CRM, SNOW, and other growth stocks are still buys at the current price simply because of operating leverage. Operating leverage explains why investors are willing to pay up for those names — but, for two reasons, it doesn’t mean investors are necessarily right to do so.

The first reason is that, no matter what operating leverage a business has, the valuation still needs to make some sense. With operating leverage, a stock can grow into a high valuation, but it can’t grow into any valuation. That was a lesson investors forgot during 2021. In particular: each of these names still trades below their peak from that year:

source: Koyfin

But the more important point is that high operating leverage makes revenue growth absolutely paramount. A 10x or 15x revenue multiple can make fundamental sense if a business can consistently increase revenue and thus drive almost exponential profit growth. If that growth shows any sign of weakness, however, the entire story changes dramatically. Profits don’t compound at the rate investors expect; over a multi-year period, that has a material impact on the stock’s valuation.

This is why SaaS stocks, in particular, can plunge on relatively tiny changes in revenue expectations. Last month, BILL Holdings BILL 0.00%↑, which provides SaaS software for back-office financial operations, lowered its full-year revenue guidance by $80 million. The stock plunged 25% the next day; BILL’s market cap declined by more than $2 billion.

Operating leverage can keep valuations elevated — but operating leverage only exists if revenue is growing. When skeptics complain that growth investors care solely about revenue, they’re not entirely wrong — they’re just missing why that revenue growth is so important.

If you enjoyed this article you can helps us by sharing it or clicking the ❤ button.

As of this writing, Vince Martin has no positions in any securities mentioned.

Disclaimer: The information in this newsletter is not and should not be construed as investment advice. Overlooked Alpha is for information, entertainment purposes only. Contributors are not registered financial advisors and do not purport to tell or recommend which securities customers should buy or sell for themselves. We strive to provide accurate analysis but mistakes and errors do occur. No warranty is made to the accuracy, completeness or correctness of the information provided. The information in the publication may become outdated and there is no obligation to update any such information. Past performance is not a guide to future performance, future returns are not guaranteed, and a loss of original capital may occur. Contributors may hold or acquire securities covered in this publication, and may purchase or sell such securities at any time, including security positions that are inconsistent or contrary to positions mentioned in this publication, all without prior notice to any of the subscribers to this publication. Investors should make their own decisions regarding the prospects of any company discussed herein based on such investors’ own review of publicly available information and should not rely on the information contained herein.

We discussed this strategy and the so-called “MoviePass economy” back in March.

Really enjoyed the reminder about the operating leverage. I read a good explanation by Howard Marks but was quite a bit of time a go and it's interesting to see applied to new things. Thanks for sharing.