Highlights:

Perion came to the public markets in 2006 as a low-quality business with a questionable business model.

The company began an effort to move into more stable and more attractive areas of the online advertising market — with some success.

But the legacy business has been crushed in 2024. Changes by a key partner led full-year guidance to be slashed.

There may be an opportunity here — but trust is key.

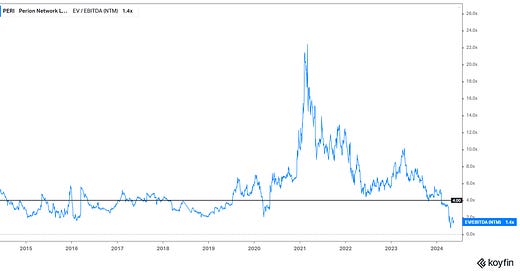

Right now, shares of adtech play Perion Network PERI 0.00%↑ are down 61% year-to-date. They trade at about 2.5x the midpoint of 2024 Adjusted EBITDA guidance. That’s the cheapest multiple in the sector, and one of the cheapest in the market. But, historically, it’s not that unusual:

source: Koyfin

Perion has been here before. Long-running concerns about the company’s business model have led investors to see significant risk in its Search segment, and significant question marks elsewhere.

Perion is now the 12th-worst performance in the entire market among companies with a market cap above $300 million. Risks are real. But echoes of the late 2010s are considerable, and equally worth noting: from 2016 lows to 2023 highs, PERI rose nearly 20x.

It’s difficult to pound the table too strongly. The valuation is attractive, but concerns about management, capital allocation, and performance in the business beyond Search all create concern. One interesting question, however, is to what extent those current concerns are being magnified by the company’s missteps in the past.

source: CodeFuel/Perion

A Questionable History

Perion began as a company called IncrediMail, founded in Tel Aviv, Israel, in 1999. Reportedly inspired by a scene from the 1996 film Mission Impossible (one founder would later say that origin story was only “partially true”), IncrediMail became the inventor of the emoticon.

IncrediMail ran on a ‘freemium’ model, and earned revenue by selling advertising and driving search engine queries on Google (now part of Alphabet GOOG 0.00%↑ GOOGL 0.00%↑) and Yahoo. The company went public in 2006, and in 2011 (after its founders had stepped down) IncrediMail looked to diversify its revenue streams. That year, the company acquired photo sharing platform Smilebox, after which it renamed itself Perion (which derives from the Hebrew word for productivity). In 2012, Perion bought Sweetpacks, a developer of apps and downloadable content, including a messaging service.

There were a couple of problems with the portfolio, however. One was that Perion was operating relatively niche products against Big Tech players. Unsurprisingly, IncrediMail and Smilebox both would lose out to offerings from Google and other ‘Big Tech’ players like Microsoft MSFT 0.00%↑ and Facebook. IncrediMail was shut down in 2020, and Sweetpacks no longer seems to exist. Smilebox remains in business, but is immaterial even for a business with a ~$600 million market capitalization1.

The bigger issue, however, is how Perion monetized its products. The downloaded applications often wreaked havoc on a user’s operating systems, with Perion fond of resetting the default search in a web browser (allowing it to then monetize those searches). A Bloomberg Television segment from 2013 noted that IncrediMail was “virtually impossible to uninstall”2; indeed, the legacy of Sweetpacks seems only to be the endless, still-live, posts from users trying desperately to get it off their computers.

Unsurprisingly, Google was not particularly thrilled about its search business being associated with questionable tactics. The search giant instituted a series of policy changes to eliminate the toolbar installations and default search resets relied on not just by Perion/IncrediMail, but the likes of AVG, Blucora and other major players.

In response, Perion tried to diversify (Google was ~70% of 2012 revenue) by signing a supply agreement with Microsoft’s Bing, and executed a massive reverse merger with Conduit, another developer that too was one of the bigger offenders of the era.

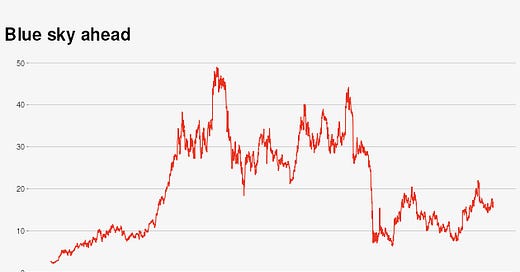

Neither tactic worked. Microsoft instituted basically the same changes, and the Conduit deal was a disaster. By 2015-2016, PERI was (as it is now) one of the cheapest stocks in the market, precisely because investors thought the business was headed for disaster. Until the pandemic arrived, that prediction seemed mostly on point:

source: Koyfin

Perion Goes Upmarket

In response, Perion spent the second half of the 2010s trying to be a better business and, perhaps as importantly, trying to prove to investors that it was a better business. At the end of 2015, the company announced the acquisition of Undertone for $180 million. Undertone developed so-called “high impact” digital advertising (think higher-quality, more dynamic, and often interactive), a notable step-up from Perion’s legacy business.

The deal didn’t actually work out: the rise of programmatic advertising commoditized the industry and disrupted Undertone’s business. In 2017, Perion took an impairment charge of $86 million, nearly half the acquisition price. But the assets acquired did provide a base for Perion to develop a legitimate business beyond search.

More acquisitions followed to augment that base. In 2020, Perion added Content IQ, the developer of a platform for digital publishers. The 2021 purchase of Vidazoo moved Perion into video monetization, and late last year the company purchased Hivestack, a programmatic digital out of home (DOOH) platform.

Even a small, not-particularly-successful deal from 2015, the $13 million purchase of MakeMeReach, turned into a social media marketing business renamed Paragone.ai. The search business re-focused on CodeFuel, serving third parties instead of the previous owned-and-operated apps like IncrediMail. Perion moved into Connected TV (CTV) advertising, and launched an audio ads offering that attracted Pep Boys and Albertsons as customers.

A new chief executive officer, Doron Gerstel, came on board in 2017, and added to the sense that this might be a different Perion. And the effort worked, both in terms of the business and the stock price.

Adjusted EBITDA was $29 million in 2017, and $169 million in 2023. Meanwhile, PERI without exaggeration was one of the best stocks in the market. From 2018 lows to 2021 highs, the stock was this close to being a 20-bagger:

source: Koyfin

Even at the highs, PERI wasn’t that expensive: the EV/EBITDA multiple peaked at about 10x in 2023. But in a adtech space where investors still have worried about competition from Big Tech, not to mention pending privacy changes from Google and Apple AAPL 0.00%↑, that multiple was not a substantial outlier.

At the very least, it was a multiple that suggested Perion was a real business. That was a departure from the stock’s treatment for most of the 2010s.

Search Bites Again

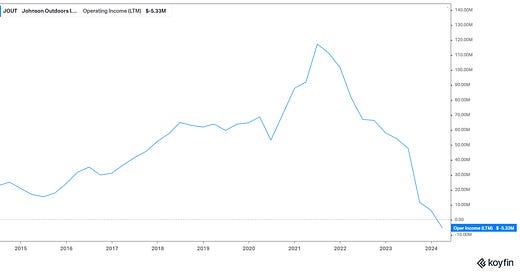

But, as it turned out, Perion can’t quite escape its history. The company has built a business beyond search, but Microsoft still accounts for 34% of total revenue in 2023; search as a whole drove 46% of revenue.

PERI got thumped after 2024 guidance. But the big plunge came last month. Perion announced preliminary results for Q1, which cited “a decline in Search Advertising activity”. More importantly, adjustments instituted by Microsoft appear to have crushed pricing, and certainly crushed Perion’s outlook:

Revenue: $860-$880 million at 2/8/24; cut 31% at the midpoint to $590-610 million at 4/8/24

Adjusted EBITDA: $178-$182 million at 2/8/24; cut 56% (!!) at the midpoint to $78-$82 million

PERI dropped 40% on the release, and hasn’t recovered (the stock has actually lost another ~4% since). Once again, the stock looks incredibly cheap: more than two-thirds of the market cap is in net cash3, and EV/EBITDA at the midpoint of guidance is 2.4x. And, once again, it seems incredibly easy to make the case that the low multiple isn’t enough, because this business is simply too risky to own.

Experience Versus Fresh Eyes

Personally speaking, one of the interesting aspects of the decline is that it highlights the pros, and cons, of having a long history with a stock.

Toward the end of the 2010s, there was a bull case for the stock. Gerstel seemed to be driving improvements in the business, the balance sheet was rock-solid, and the overall digital ad space was growing. But that bull case was a much easier sell to someone who didn’t know the history that well — or at all.

Those who did know that history, myself included, knew Perion as a company whose business model literally had been “distribute apps to older users4 who likely will lack the technical know-how to remove those apps”. Even with a new CEO, and a new business, and seeming downside protection from the cash balance, that perception was nearly impossible to overcome.

Conversely, someone who came to the stock with fresh eyes could, perhaps, see that opportunity more clearly. The risk/reward did seem to favor an investment: Perion might well blow up in a competitive ad space, but if it succeeded the upside was multiples of the stock price at the time. And, of course, Perion did succeed, and to some extent still has: even with the recent plunge, the stock is up 183% since the end of 2016, and +327% from that year’s lows.

There’s obviously an anchoring bias on both sides. Seeing Perion for the first time in 2011 colored the opportunity in 2018. Seeing Perion for the first time in 2018, however, meant seeing a ridiculously cheap headline valuation, with the, shall we say, questionable activities of the past not really relevant to the bull case at the time.

And there was a massive opportunity in the last few years of the 2010s, even for investors who sold too early (or too late). At the same time, a deeper knowledge of the company’s history might well have saved investors here in 2024.

It’s not hard to see in commentary from both investors and executives a rather blasé attitude toward the revenue concentration at Microsoft, and the danger in such a lopsided partnership. (Quite obviously, Perion needs Microsoft far more than Microsoft needs Perion.) But those who had seen the impact of the Google relationship on PERI stock likely had a better sense of the risk. Overall, fresh eyes won but only if they timed it right.

PERI Looking Forward

And after the plunge, this is kind of the same story. PERI again looks ridiculously cheap at less than 3x EV/EBITDA. The downside protection from the cash seems reasonably intact, particularly given management seemed emphatic on the Q1 call that Perion would implement a previously authorized $75 million repurchase effort as soon as possible.

The Search business has taken a huge hit, of course, but there’s still a pretty broad portfolio beyond Search:

source: Perion Q1 2024 presentation

And the sharp cut in guidance itself de-risks the story somewhat at the lower valuation. Simple math dictates that further changes in the Microsoft agreement can’t be that material. Microsoft was 34% of revenue in 2023; if it’s mostly responsible for an expected ~20% decline in total revenue in 2024, its share of total revenue this year is going to be substantially smaller.

In a weird way, Perion’s history shouldn’t really matter anymore: the risk that investors have been dreading for about 15 years has finally played out. We all pretty much knew Search was heading to zero eventually; the debate was really over when that was, how much cash Perion could generate in the meantime, and what it would do with that cash.

And that’s where the debate should be now. Fundamentally it seems to favor Perion. Even if Microsoft revenue goes to zero, PERI is probably trading at a mid- to maybe high-single-digit EV/EBITDA multiple, and at worst mid-teens relative to earnings and normalized free cash flow when backing out net cash.

That’s essentially the 2019 bull case redux: Search is a melting ice cube, but even at a low (or even zero) valuation, Perion as a whole is cheap enough given the strength elsewhere in the business. There’s even a new CEO, as there was five years ago. In August, Gerstel was replaced by Tal Jacobson, an internal promotion. It bears repeating: that 2019 bull case was proven spectacularly correct.

What Exactly Is Going On With Perion?

I personally missed that bull case, because I didn’t quite trust the business. As a result, I’m somewhat cognizant of making the same mistake again. There absolutely is a scenario in which investors are overreacting here. More importantly, it’s not that difficult to look out 14-plus months, to the Q2 2025 report, and see a company that (with some help from easy year-prior comparisons) is returning to growth, and fully focused on building out a broad, unified, adtech platform that can really compete.

Again, the market until recently was treating this like a real business. There are truly intriguing aspects. Management has cited blue-chip customers like Lululemon LULU 0.00%↑, Anheuser Busch InBev BUD 0.00%↑, and Alberstons, among others. The company’s SORT (Smart Optimization of Responsive Traits) technology aims to drive personalized advertising despite the end of the cookie, and SORT 2.0 is expanding into CTV. Quantitatively and qualitatively (with the caveat that these businesses all have a somewhat “black box” aspect from the outside), it seems like Perion is a significant, legitimate, player in adtech.

But the catch is that, even recognizing that bias, Perion’s Q1 report doesn’t quite add up. The story from management in the preliminary release in April and after Q1 results was that the Microsoft changes begin in the second quarter. This will hit search revenue and, as chief financial officer Maoz Sigron put it on the call, “to a limited extent, a reduction in video activity”.

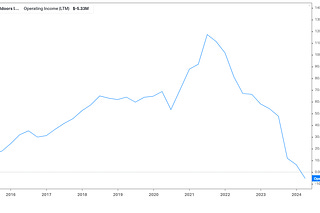

The problem, however, is that Q1 was a disaster. Perion didn’t give guidance for the quarter, but for the full year (at the midpoint) it projected growth in revenue of 17% and in Adjusted EBITDA of 6%. In Q1, advertising revenue fell 5% year-over-year, driven by video (where Perion has shifted inventory to display); overall Adjusted EBITDA plunged 35%.

Per management, the Microsoft changes didn’t hit the search business in the quarter. Indeed, Search revenue rose 26%. But TAC (traffic acquisition costs) jumped, and margins collapsed — with at least some of the pressure coming ex-Search.

Indeed, it looks like Perion almost certainly would have had to lower its full-year outlook even without the Microsoft changes.

Sigron did say video would bottom after Q2, which likely means the company expected (and expects) a more back-loaded year, but at the very least Perion is playing from behind. And it’s worth noting that normalized EBITDA remains below the ~$80 million guidance for 2024, since that includes a quarter for Search that ended before the Microsoft changes. On a run-rate basis, this is probably closer to a $65-$70 million business at the moment, though to be fair that is still a valuation of about 3x EBITDA.

Trust And The Value Trap/Value Play Debate

There was essentially zero commentary from management after Q1 that explained why the quarter was weak — or even acknowledged that weakness at all. The tone was that the Microsoft changes were a setback, but one that Perion will eventually be able to overcome. That may be true, but if so Q1 was hardly a strong first step in that process.

And the problem is that a stock like PERI at this point boils down to trust in management. The company does have $480 million in gross cash and investments — but no apparent plan to use it, beyond the aforementioned buyback. $200 million-plus comes from equity offerings executed back in 2021; the second in retrospect was a good trade (Perion sold $180 million in shares at $21.50) but remains questionable from a capital allocation standpoint. M&A still seems to be the focus, as has been the case for a decade and a half: Perion last bought back stock in 2009 (it repurchased ~$1 million at March lows), and changed to a firm policy of not paying dividends the following year.

There’s a real sense that the business just isn’t good enough, in terms of operations and in terms of being shareholder-friendly. The ability of Perion to change that perception and regain credibility with investors can drive shareholder returns: Gerstel did exactly that in his six-year stint atop the company. That (along with bottom-line growth, of course) was enough to get PERI’s EV/EBITDA multiple from absurdly cheap to reasonable, and that was a material driver of the 1,800%-plus returns the stock posted in seven years.

History absolutely can repeat here. Simply executing on the buyback would likely put some capital allocation concerns to rest, though a more aggressive policy at this point would be welcomed. (If the company’s own stock isn’t a great investment at under 3x EBITDA, when is it a great investment? And what acquisition can possibly be a better alternative?)

It’s always difficult to jump into these situations in the small- to mid-cap world. Of course, it’s always tempting as well. As PERI shows, the upside can be tremendous if there is a coherent, rational, and realistic strategy for improvement.

That strategy may exist here. But, to be honest, I don’t see it coming out of Q1. That may be the wisdom gained from following PERI for over a decade — or it may be making the same mistake twice.

As of this writing, Vince Martin has no positions in any securities mentioned.

Disclaimer: The information in this newsletter is not and should not be construed as investment advice. Overlooked Alpha is for information, entertainment purposes only. Contributors are not registered financial advisors and do not purport to tell or recommend which securities customers should buy or sell for themselves. We strive to provide accurate analysis but mistakes and errors do occur. No warranty is made to the accuracy, completeness or correctness of the information provided. The information in the publication may become outdated and there is no obligation to update any such information. Past performance is not a guide to future performance, future returns are not guaranteed, and a loss of original capital may occur. Contributors may hold or acquire securities covered in this publication, and may purchase or sell such securities at any time, including security positions that are inconsistent or contrary to positions mentioned in this publication, all without prior notice to any of the subscribers to this publication. Investors should make their own decisions regarding the prospects of any company discussed herein based on such investors’ own review of publicly available information and should not rely on the information contained herein.

The business hasn’t been discussed on a conference call since 2016, and is no longer mentioned in securities filings, either.

The segment doesn’t appear to be available online; I quoted it in a Seeking Alpha article I wrote at the time.

That’s net of earnout payments for acquisitions, which appear to be paid in stock rather than in cash.

Perion called them “second-wave adopters”.

Gerstel's sudden retirement was, at least in retrospect, a huge red flag and outstanding sell/short signal.

PS: any thoughts on the AGS deal?