The Problem With P/E Multiples (And What To Do About It)

SentinelOne shows the challenge of relying on P/E ratios alone

Editor’s Note: This is the second article in our Fundamentals series. If you enjoy this series, let us know in the comments.

By one measure, cybersecurity stock SentinelOne S 0.00%↑ is the most expensive in the entire market. Based on Wall Street estimates, the company trades for over 5,000 times its earnings for the following fiscal year1 (a figure known as “forward earnings”). It’s the highest forward P/E multiple for any U.S.-listed stock. Based solely on this metric, SentinelOne stock appears uninvestable.

After all, growth stocks like Palantir Technologies and Shopify trade at just 65x their forward earnings. Meanwhile, a stalwart like AT&T is valued at just 5.7x forward earnings — a multiple one four-hundredth of SentinelOne. Given those options (and thousands of others), who in their right mind would pay such an insane multiple for SentinelOne?

Of course, SentinelOne’s forward multiple is a mathematical artifact caused by the company ever so slightly crossing into profitability in fiscal 2025 (the company’s fiscal years end in January, so fiscal 2025 begins in February 2024). S stock has the highest forward multiple in the market because SentinelOne has perhaps the lowest positive estimated earnings in the entire market. Per Koyfin, the average estimate for adjusted net income in FY25 is just $1 million. Hence, the $5.1 billion market cap leads to a forward multiple over 5,000x.

That mathematical artifact has little effect on the valuation of SentinelOne stock. All else equal, the business would not be materially less valuable if analysts expected a $1 million loss next year instead of a $1 million profit. The extreme nature of SentinelOne’s P/E multiple is useful for thinking through what a price to earnings multiple actually means.

Lower P/E = Better…Right?

If ABC stock is trading at 10x earnings, and XYZ is trading at 30x earnings, it would stand to reason that an investor has a better chance of garnering substantial returns with ABC.

Obviously, it’s not an absolute rule that a lower P/E is always better: if it were, no stock would ever be priced at a high P/E multiple. Investors would simply sell the highly valued stocks, buy the ‘cheaper’ ones, and eventually every stock in the market would settle at the same multiple.

Quite clearly, such a scenario is impossible. Still, for many investors, a low P/E multiple seems better. The words commonly used to describe those multiples reflect that fact. A stock trading at, say, 8x earnings is often described as “cheap”; one trading at 80x earnings is almost inevitably termed “expensive”.

That construction, however, can be incredibly damaging. A P/E multiple, on its own, has absolutely no bearing on whether a stock is attractive. A stock that trades for 10x earnings could be an attractive long if an investor believes earnings are likely to grow over the mid-term. It could be a screaming short if the business has peaked for good or, as was the case for so many retail stocks in 2021, if the 10x multiple is based on earnings inflated by short-term factors like government stimulus and sharply lower travel and restaurant spending. Similarly, a stock at 80x earnings can absolutely be ‘cheap’ if future prospects are strong enough.

The P/E multiple is only a useful piece of information in conjunction with a sense of the trajectory of earnings. And even then, it’s far from foolproof. It’s worth remembering that the concept of earnings itself is an accounting construct. It’s usually a logical and useful construct, but it’s a construct nonetheless, and there are instances where earnings aren’t telling the whole story — or are actually telling the wrong story.

Real estate investment trusts, for instance, are rarely if ever valued on earnings. The accounting treatment surrounding real estate creates high levels of depreciation, a non-cash expense which depresses earnings but has no impact on cash flow. Instead, REITs nearly always use a metric known as ‘funds from operations’, which adjusts net earnings to better reflect the true health of the business.

Back in July, we recommended shares of Seneca Foods. In one fiscal year, an accounting decision related to the company’s inventory resulted in earnings per share of either $4.20 or $13.48. Quite obviously, SENEA stock looks very different using one figure instead of the other. Which figure is correct? Neither. Again, earnings is an accounting construct that aims to reflect reality, but occasionally does so rather imperfectly.

Looking Forward

This is not to say that the P/E is useless. Rather, investors need to understand its limitations. The multiple itself tells investors very little about the attractiveness of a stock. Even combining the understanding of that multiple with underlying profit growth still leaves some holes.

For instance, earnings may have grown looking backward, but what does that mean going forward? In our first piece in this series, on Walgreens Boots Alliance, we noted that when the stock peaked in 2015, essentially every investor on Earth believed the company’s profits would continue to grow. For a variety of reasons ranging from management missteps to a surprising lack of negotiating power with insurance companies, that didn’t happen.

But for many stocks, the cause of earnings movements tend to be far more external than internal. As of this writing, the average Wall Street analyst expects full-year 2023 earnings per share for ExxonMobil to decline by one-third against the 2022 figure. That decline doesn’t mean that ExxonMobil is a declining business, or that XOM stock is a short, or that its 11.7x P/E multiple is too high. Rather, oil and (particularly) natural gas prices have moved against the company this year. Investors need to weigh the external just as much as the internal.

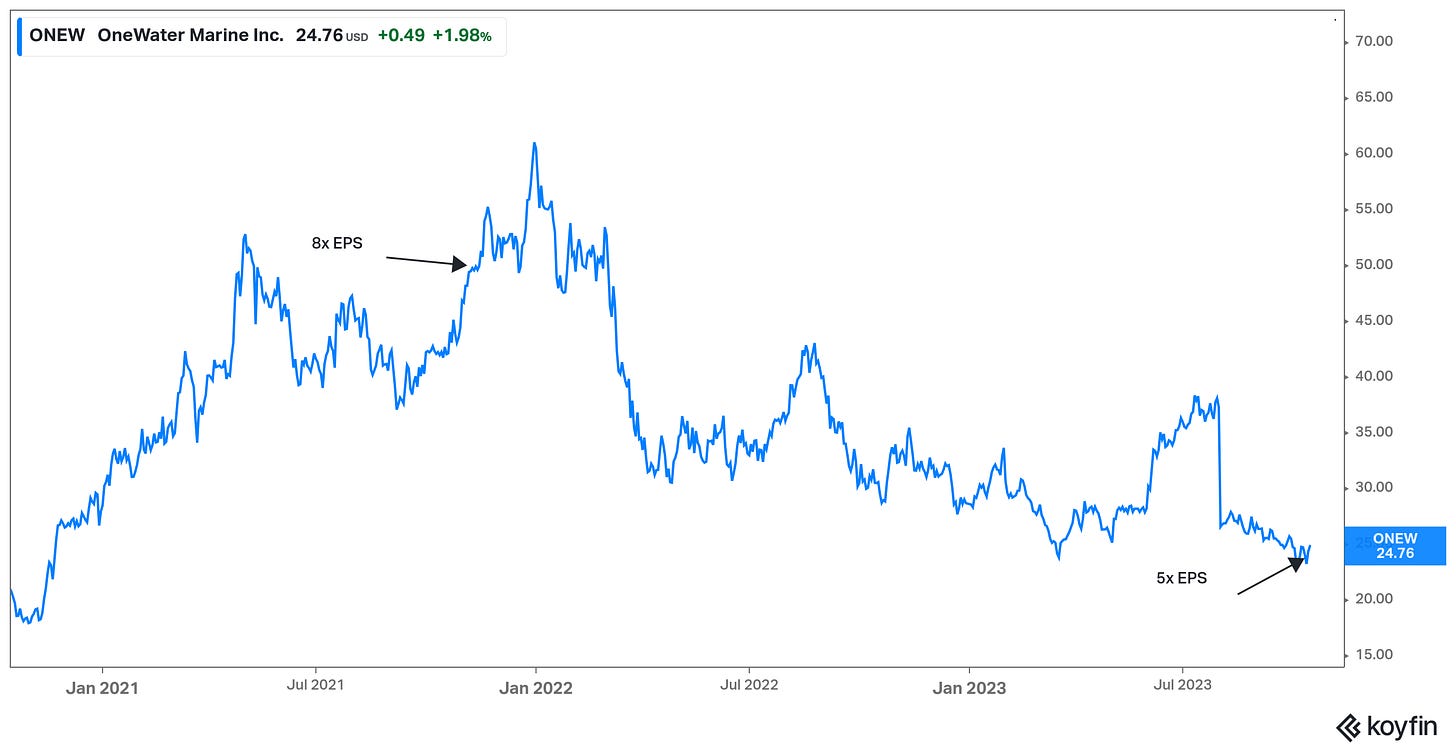

Similarly, the manufacturers of boats and recreational vehicles saw tremendous growth in 2021, as consumers redirected government stimulus and travel spending into big-ticket purchases. In its fiscal year 2021, boat dealer OneWater Marine saw its sales increase 20% year-over-year. Earnings per share rose 151%. Yet, after the report in November, ONEW traded at just 8 times FY21 earnings per share.

Given reported growth, that multiple is preposterous. Looking forward, however, investors realised that earnings would decline as normalization arrived. Indeed, OneWater expects EPS of $4.45-$4.70 in fiscal 2023, and ONEW stock has fallen by more than 50% since the Q4 FY21 release nearly two years ago.

The Math Can Get Weird

Many growth stocks in recent years have seen hugely elevated P/E multiples. Some have no P/E multiple at all, because there is no ‘E’ (at least, no positive ‘E’) because the companies remain unprofitable. Uber went public in 2019 at an $82 billion valuation. The company will report its first full-year profit this year, and even that on an adjusted basis.

But the existence of unprofitable public companies itself provides some context for the limitations of P/E multiples. Many investors instinctively dismiss a stock that trades for 80x earnings or 150x earnings as ‘too expensive’. But almost by definition, that business has some value, even if it isn’t profitable yet. If a business with no profits can be worth $82 billion2, then a business with some profits can support a multi-billion-dollar market cap as well.

For businesses that are narrowly profitable thin profit margins inflate P/E in a way that makes them look more expensive than they potentially are. Again, SentinelOne is a perfect example of this. A 5,000x-plus earnings multiple sounds ridiculous. But if its net profit (as estimated by Wall Street) were lower by just one-quarter of a percentage point of revenue, there would be no earnings. In that situation, an investor might instead look at, say, enterprise value to revenue, and see a 5x multiple as reasonable (or at least more reasonable) relative to other cybersecurity stocks.

Those thin profit margins also set the stage for rapid growth. If SentinelOne can improve its profitability by just one percent of revenue, its net earnings rise elevenfold (roughly speaking, 0.1% of revenue to 1.1% of revenue). And given that platform operators like SentinelOne can expand their profit margins quickly, investors can model aggressive profit expansion in short order. Move net income to 5% of revenue from 0.1%, and double that revenue, and earnings increase by about 100x. Suddenly, a stock trading at 5,000x next year’s earnings might only be trading at 50x 2026 earnings — with many, many, more years of growth ahead. Given that model, an investor might reasonably believe that a stock with the highest P/E multiple in the entire market is, in fact, ‘cheap’.

Think Through The Model

The broad point here is that P/E is a rule of thumb. It’s fair to assume that in most cases, a 50x P/E multiple implies that the market is pricing in quite a bit of growth and a 5x P/E multiple suggests the business is headed for a decline. But the key phrase is “most cases”. There are exceptions to every investing rule. And it’s this fact that makes screening for stocks based on the P/E ratio so problematic.

Investors can’t blindly use a P/E multiple as a marker of valuation. Instead, the P/E multiple should be used as a marker of expectations: the expectations the market has for the growth potential of that business.

We’ve heard investors argue for low P/E stocks using a simple analogy: if a stock trades at six times earnings, then in six years, the shareholder gets her money back. But that’s not true (even setting aside the fact that she doesn’t actually get the money back in cash). What a 6x multiple usually suggests is that the market thinks profits are going down. And if those profits go down, the company isn’t earning back its market cap over six years. If they go down quickly, the company may never earn its market cap back at all.

Indeed, at least during the 2010s, low P/E stocks significantly underperformed their high P/E counterparts. That does appear to be a change from 20th century results, and if so the question is why? Zero or near-zero interest rates, which in theory make growth stocks more attractive3, are one possible cause. Another is the rise of software and other tech businesses, which have higher profit margins and less exposure to macroeconomic cycles than did industrial giants a few decades earlier.

But in any environment, there isn’t one right answer. What P/E multiples provide is an imperfect, high-level guide to the growth investors are pricing into a stock. They are a starting point for research, not a key component of that research. A step for understanding, roughly speaking, where the market expects a business to go. It’s up to the individual investor to figure out if the market is right or wrong — and invest accordingly.

As of this writing, Vince Martin has no positions in any securities mentioned.

Disclaimer: The information in this newsletter is not and should not be construed as investment advice. Overlooked Alpha is for information, entertainment purposes only. Contributors are not registered financial advisors and do not purport to tell or recommend which securities customers should buy or sell for themselves. We strive to provide accurate analysis but mistakes and errors do occur. No warranty is made to the accuracy, completeness or correctness of the information provided. The information in the publication may become outdated and there is no obligation to update any such information. Past performance is not a guide to future performance, future returns are not guaranteed, and a loss of original capital may occur. Contributors may hold or acquire securities covered in this publication, and may purchase or sell such securities at any time, including security positions that are inconsistent or contrary to positions mentioned in this publication, all without prior notice to any of the subscribers to this publication. Investors should make their own decisions regarding the prospects of any company discussed herein based on such investors’ own review of publicly available information and should not rely on the information contained herein.

Some sources use estimated earnings for the next four quarters, rather than the following fiscal year, but the full-year approach appears to be more common.

To be fair, that valuation was too high; incredibly, Uber still trades modestly below the $45 price of its initial public offering.

Lower interest rates should make future profits more valuable, because the alternative of putting cash in demand deposits or government bonds pays so little. Since high PE stocks usually provide ownership of fast-growing companies, they have more profit further out in the future, and thus are more attractive when interest rates are low and less so when rates are high. As the recent performance of tech stocks shows, however, this, too, is a rule of thumb with more than a few exceptions.

This series is a good read. Would be cool to cover other stock picking / analysis fundamental concepts